Left of Clinical: A New Approach to Veteran Wellness

Veteran suicide rates have remained stubbornly flat for nearly two decades despite billions invested and countless initiatives. VA’s 2024 Annual Report tallied 6,407 veteran suicide deaths in 2022 (17.6 per day), underscoring how little progress the nation has made since 2001. The current model largely waits until veterans are already in crisis, and by then, the tools left are prescriptions and clinical interventions that treat symptoms but rarely restore purpose and connection. We’ve written extensively about the failure of progress in this regard, including our Suicide Prevention page, our survey addressing this topic, and our 2025 Update to our State of Veteran Suicide report. At Mission Roll Call, we believe it is time to test a different path.

In this three-part series, we explore the concept of moving “Left of Clinical”—acting earlier, while veterans are still strong and connected, rather than waiting until isolation and despair drive them to the edge. Our latest national survey of nearly 2,300 veterans and family members makes the case for preventive wellness: interventions that keep veterans engaged, purposeful, and resilient long before they ever need a prescription or diagnosis.

In Part One, we examine what veterans lose in transition and why connection matters. In Part Two, we look at what preventive interventions could actually look like in practice. And in Part Three, we map out how the VA, Congress, and community partners can work together to build a system that finally bends the curve on veteran suicide.

Part One: Veterans Value Preventive Connectedness

At Mission Roll Call, we listen to what veterans are telling us and bring those voices directly into the national conversation. In September 2025, we conducted a survey focused on a question that does not often get asked: what would it look like if the VA, and indeed our entire veteran care system, invested more heavily in preventive wellness programs that keep veterans strong and connected before they ever need medical intervention?

The message is unmistakable. Veterans are asking for a broader array of options that they can tailor to their specific needs, with greater say and influence over those decisions. But here is the harder truth: veteran suicide statistics have remained flat for nearly two decades.

Despite billions of dollars invested, the model we rely on is not moving the needle. We continue to meet veterans at the point of crisis, and too often the only tools available are prescriptions and clinical interventions that treat symptoms without addressing root causes. Preventive wellness offers a new and largely unexplored pathway — one that can help veterans stay connected, purposeful, and healthy long before they ever reach the edge of crisis.

With suicide rates unmoved and trust in current approaches strained, it’s time we begin holding serious discussions about how to achieve these aims.

What “Left of Clinical” Means

The phrase “left of clinical” comes from the same mindset that has guided military training and operations for generations. In military planning, being “left of” something means acting before the moment of crisis. In veteran health, being “left of clinical” means recognizing and addressing the challenges of transition and post-service integration into society long before they result in harmful self-talk or require a diagnosis or prescription.

Today, too many veterans only enter the care system once their struggles have reached a breaking point. Typically, by this point, isolation has taken root, stress has hardened into anxiety, and coping mechanisms have turned unhealthy. Too many veterans respond at that stage with alcohol or medication, or both, sometimes a cocktail of drugs prescribed with the best of intentions, but ultimately are not designed for prevention or long-term wellness and often create long-term dependencies and addiction. A case of the cure being worse than the disease.

Our latest survey gives weight to what many of us already know instinctively: veterans want healthier options long before they get to that point.

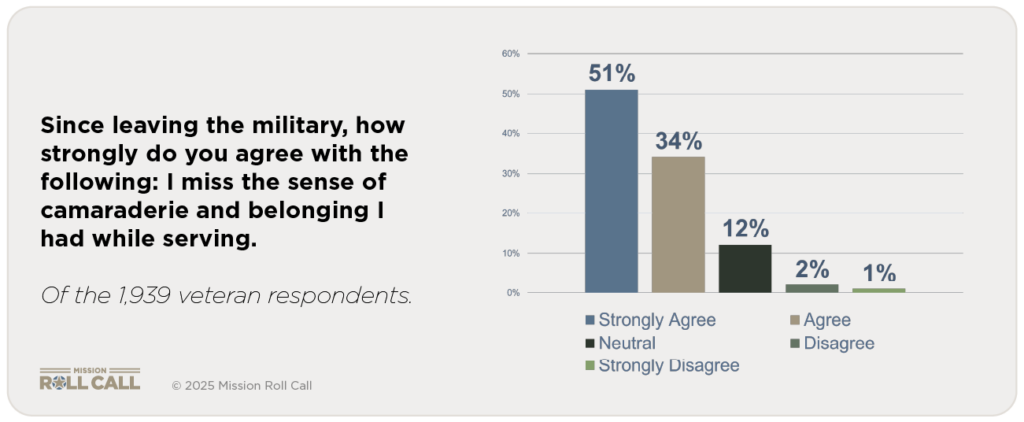

The strongest signal from our September survey is about what veterans value most after leaving the military. Almost 86 percent of respondents said they strongly agree or agree that they miss the sense of camaraderie and belonging they had while serving. Less than 3 percent disagreed. The bond of shared experience is not just a fond memory. It is the anchor that many veterans find missing in civilian life.

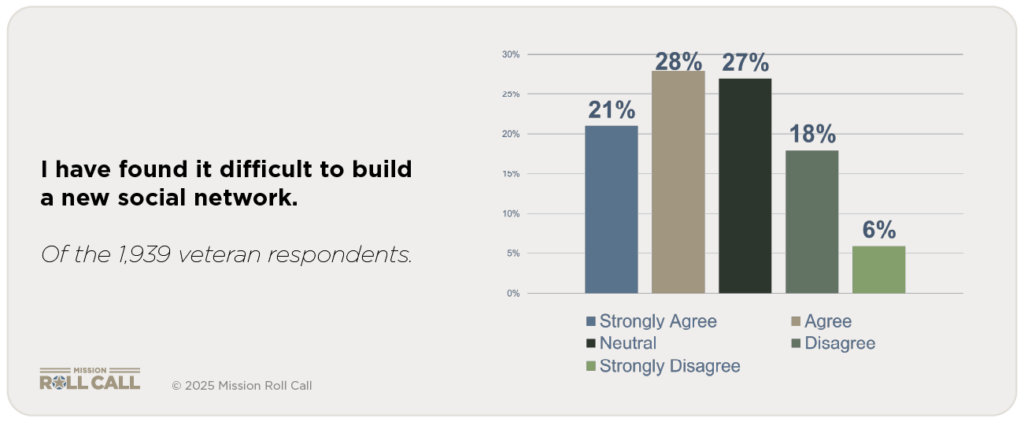

That loss has real consequences. Nearly half (49.5 percent) said they agree or strongly agree that they have found it difficult to build a new social network since leaving the military. Another 27 percent were neutral, meaning only about one in four veterans feels they have successfully rebuilt the same trust and community they once had in uniform. This is where isolation begins, and where stress compounds.

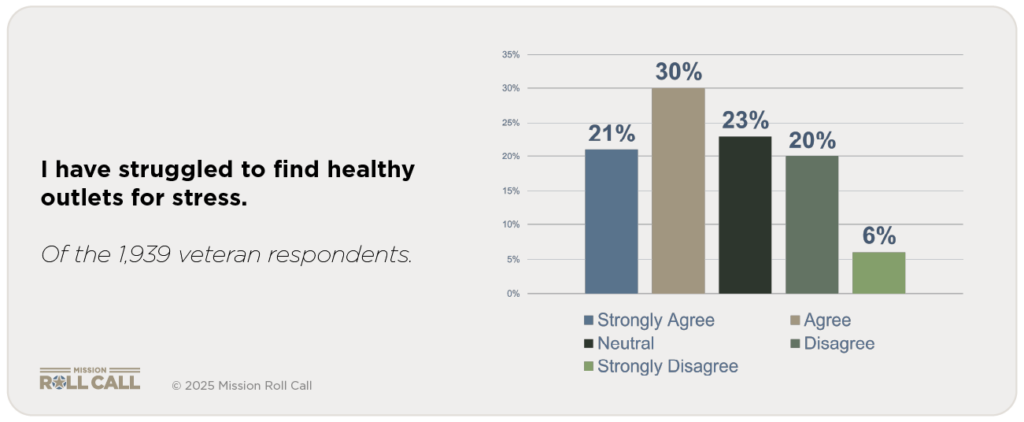

The same pattern appears when veterans talk about coping. Just over 50 percent said they have struggled to find healthy outlets for stress. A quarter were neutral, and only a quarter disagreed. Most veterans live in an environment where the old ways of managing stress—team, mission, shared purpose—are gone, and nothing equally strong has replaced them.

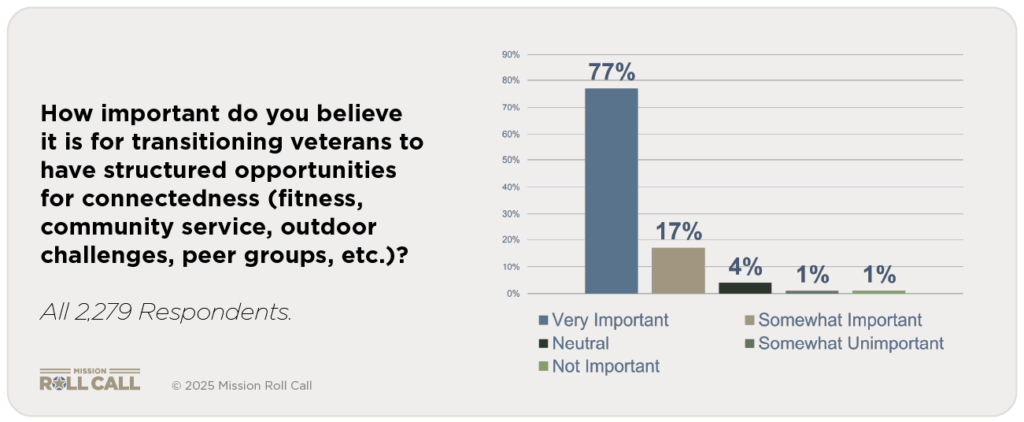

When asked directly, veterans did not hesitate about what they want instead. Over 95 percent said it is very important or somewhat important for transitioning service members to have structured opportunities for connectedness. Less than 1 percent said such opportunities are not important. In other words, nearly every veteran sees connectedness as essential to their well-being.

This matters because of where the absence of connectedness leads. Without community and purpose, isolation grows. Isolation becomes stress. Stress becomes unhealthy coping. And too often, the VA meets veterans for the first time only when they are already in crisis. At that point, the response is often medication—sometimes multiple prescriptions that dull symptoms without addressing the root cause: the loss of belonging.

Veterans are telling us they want something different. They want opportunities to connect, to be part of a team again, to build resilience before they ever need a prescription. They are asking for prevention that sits left of clinical—because they know that is where real strength is rebuilt.

The next question is obvious: what would those preventive wellness opportunities actually look like? In Part Two, we turn to the survey results that show which interventions veterans say they want most, what keeps them out of those programs today, and how the system can remove those barriers.