The State of Veteran Suicide (2025 Update)

Introduction

For decades, the issue of veteran suicide has hovered just beneath the surface of national discourse—tragic, persistent, and alarmingly consistent. Each year, thousands of former service members die by suicide, and the message is tragically clear: we are losing too many of our nation’s heroes after they come home.

Those thousands of lives are not just numbers. They are the men and women who served our nation and who, too often, are left to struggle in silence. These statistics are not new. They echo the same refrain we’ve heard for years. But even slight shifts in data and emerging trends remind us that this crisis is dynamic, and that every year brings fresh opportunities—and obligations—to act.

In this updated report, Mission Roll Call outlines what has changed, what progress has been made, and where we still fall short. With new legislation, shifting budget priorities, and a continued national conversation about mental health, there is hope. But hope alone will not solve the problem. It takes policy, persistence, and the collective will of communities across the nation.

What has changed?

While many suicide-related statistics remain troublingly static, new data and federal actions present important developments.

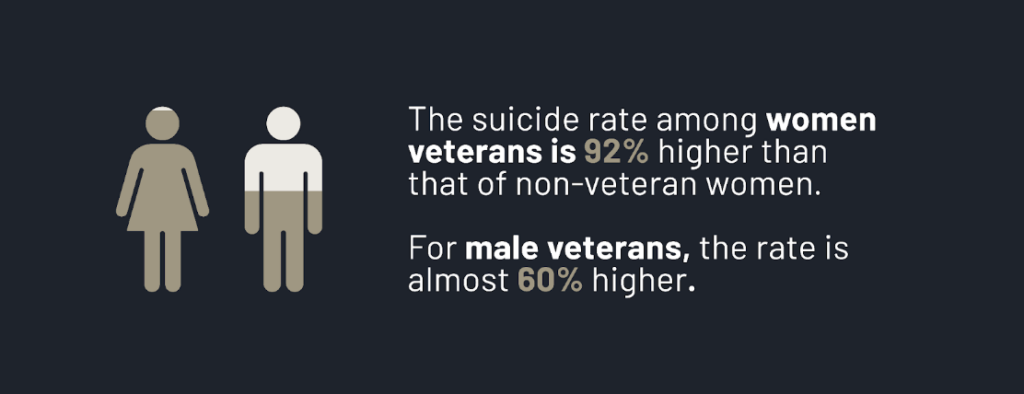

For instance, mental health disparities between veterans and civilians continue to widen. The suicide rate among women veterans is 92% higher than that of non-veteran women. For male veterans, the rate is almost 60% higher. These gaps demand continued focus.

Also worth noting is a growing sense of moral injury and disillusionment among some post-9/11 veterans. Recent data found that 73% of veterans polled felt the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan negatively impacted the way they view America’s legacy in the Global War on Terror – a 3% increase from last year.

On a positive note, the annual VA budget has dramatically increased. Over the past decade, the proposed VA budget has increased by 125.3%, reaching $369.3 billion. The VA budget is now more than six times its 2001 budget of $45 billion. This funding is critical and will go toward much-needed health care, benefits, housing and insurance for veterans. Additionally, in May 2025, the Trump administration highlighted the need to honor veterans, stating that the federal government “should treat veterans like the heroes they are.” As part of this commitment, the administration signed an executive order to combat veteran homelessness by establishing the National Center for Warrior Independence, aiming to house 6,000 veterans by 2028.

This kind of momentum is crucial. But funding alone is not enough if it doesn’t translate into real, effective support on the ground.

Veteran suicide by the numbers

According to the VA’s most recent National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (2024), an average of 17.6 veterans die by suicide every single day. Although this figure is widely accepted, the real number may be even higher.

An Operation Deep Dive report by America’s Warrior Partnership (AWP) suggests that veteran suicides are significantly underreported. AWP suggests that as many as 24 veterans die by suicide per day, with an additional 20 dying by “self-injury mortality,” often overdoses. This totals to a staggering 44 veterans who die by suicide per day, about 2.4 times more than the VA’s estimate.

Mission Roll Call acknowledges the VA’s cautious approach in classifying overdoses as suicides. But the discrepancy between these two reports highlights a deeper issue: we need better data, better definitions, and more transparent reporting. Without accurate data, prevention strategies will always fall short.

Even more urgently, the first two years after leaving active duty remain a high-risk period. Veterans early in their transition often face isolation, unemployment, housing instability, and confusion navigating care. Research from the American Enterprise Institute highlights that the most effective point of intervention is during these first two years, when veterans are actively transitioning, and that critical interventions such as mentoring and job preparation can significantly ease this process. The Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs must work together more seamlessly to ensure no service member falls through the cracks during this vulnerable time.

Legislative wins: The Elizabeth Dole Act

One major shift in the effort to end veteran suicide comes with the passage of the Elizabeth Dole 21st Century Veterans Healthcare and Benefits Improvement Act. Passed in late 2024, the act is a major legislative win and is the most significant expansion of VA services since the PACT Act. Building on the framework of the PACT Act, which addressed toxic exposure-related healthcare, the Elizabeth Dole Act takes a more holistic approach—expanding VA services to support not just veterans, but also their families and caregivers.

The Elizabeth Dole Act directly benefits veterans by streamlining the disability claims process and expanding job training and employment programs to help them transition to the civilian workforce. It will also increase access to mental health services and support homelessness prevention efforts by identifying at-risk veterans and providing them with funding for job training and substance abuse treatment. The act will also address homelessness by allowing the VA to supply veterans with necessities like food, bedding, hygiene products, and transportation to medical appointments.

On top of serving veterans, the act also serves the 7.8 million military and veteran caregivers – often spouses, parents and dependents – who sacrifice their time and even their personal lives to care for their loved ones. The legislation supports caregivers by expanding caregiver support programs and access to at-home and community-based services across VA medical centers. However, one of the most helpful changes for caregivers is the mental health care grant program, which will fully fund the cost of nursing home care for veterans seeking noninstitutional care alternatives. This could provide eligible veterans and their families thousands of additional dollars per month, easing burdens for aging and disabled veterans and their caregivers.

What work still needs to be done?

Despite this progress, there is more to do. For instance, post-traumatic stress (PTS) remains a leading factor in veteran suicide. Among veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan, 15% experience PTS symptoms in any given year, and about a third are estimated to face PTS at some point in their lifetime. Due to its prevalence, PTS is now known as the “signature wound” of the Global War on Terror. Difficult-to-navigate health care only exacerbates this issue, and is unfortunately common: Nearly 45% of veterans experience delays or postponement related to health care services at VA facilities. For instance, the Washington, D.C. VA medical center, which services over 125,000 veterans, has a wait time of 13 days for primary care — but for new patients this time jumps to 43 days. Mental health care is even worse, with 19 day wait time for existing patients, and 53 day wait for new patients, who may be experiencing true issues.

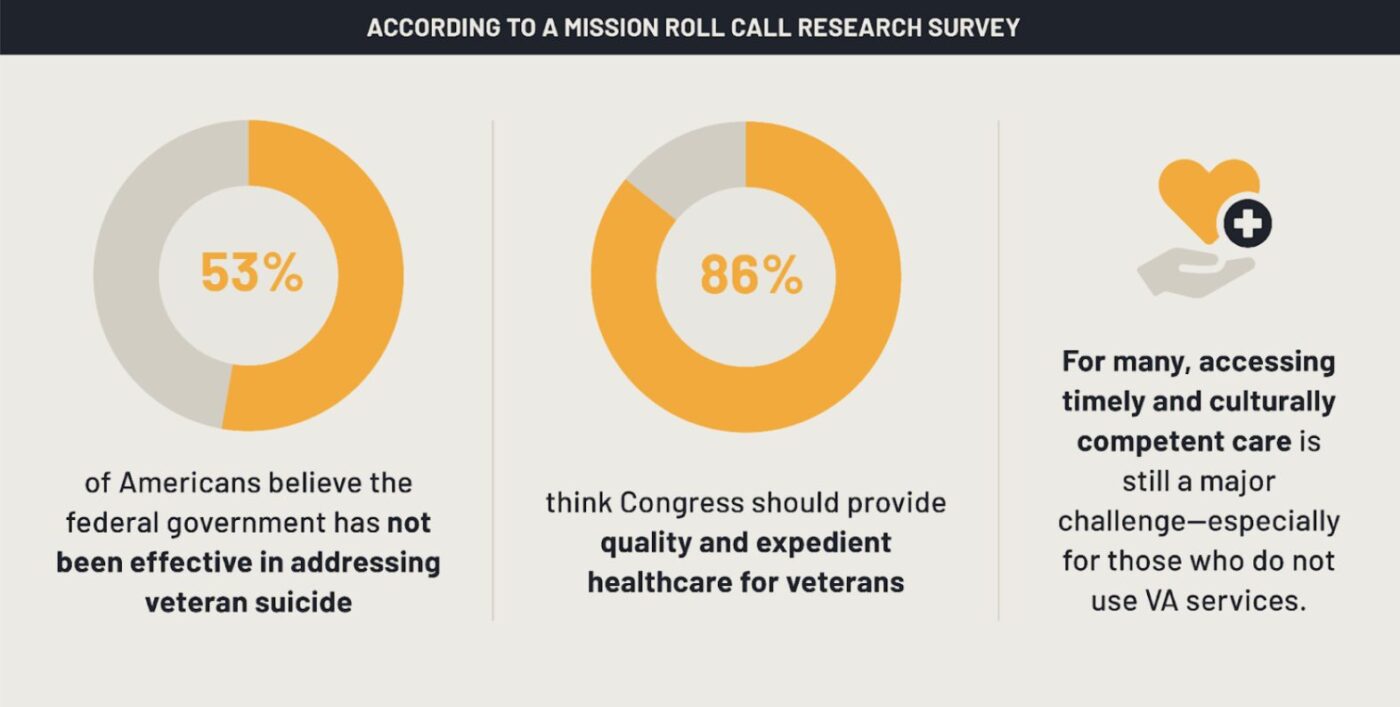

According to a Mission Roll Call research survey, 53% of Americans believe the federal government has not been effective in addressing veteran suicide, and 86% think Congress should provide quality and expedient healthcare for veterans. For many, accessing timely and culturally competent care is still a major challenge—especially for those who do not use VA services.

In our 2024 State of Veteran Suicide report, we highlighted several systemic challenges: inconsistent access to care, gaps in transition assistance, and a dangerous stigma around asking for help. Unfortunately, these issues remain largely unresolved. Legislation like the Elizabeth Dole Act is a significant step toward ensuring veterans and their families receive all the support they need, but it must be part of a sustained, broader commitment to veteran suicide prevention.

How can we help?

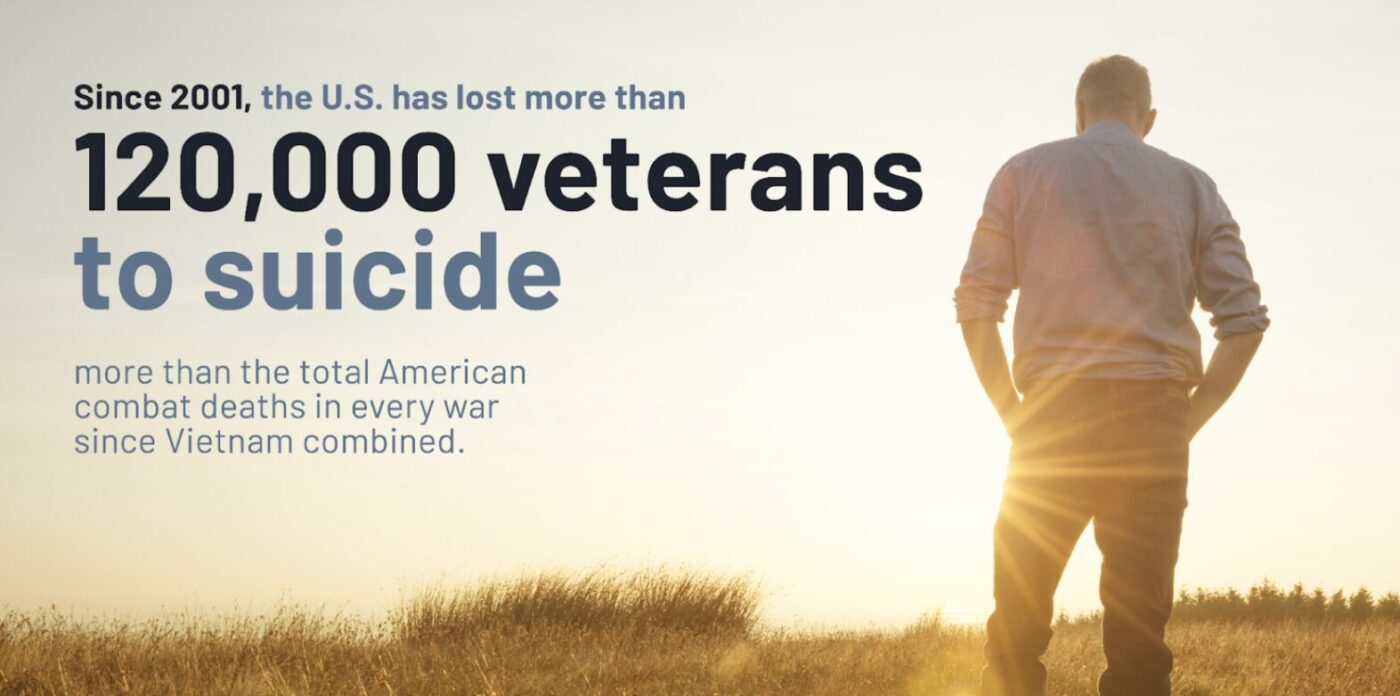

Since 2001, the U.S. has lost more than 120,000 veterans to suicide—more than the total American combat deaths in every war since Vietnam combined. This is not a crisis we can address passively. It requires the full force of government, community, and individual action. Since 2001, an alarming 6,000 to 6,700 veterans have died by suicide each year.

Here are some of the ways we can all help:

- Increase mental health access. This means more providers, shorter wait times, and non-pharmacological options like Boulder Crest’s posttraumatic growth program.

- Combat stigma. Many veterans still view asking for help as a weakness. We must continue normalizing mental health conversations in the military community—and beyond.

- Strengthen transition support. Leaving military service should not mean entering a void. Every veteran needs a roadmap—and a community—during their first years of civilian life.

- Support local organizations. Nonprofits like Mission 22, Boulder Crest, and America’s Warrior Partnership are on the frontlines of suicide prevention.

- Re-think suicide prevention models. Suicide rates have remained unchanged after decades of war, and in many ways, mental health and suicide prevention methods have also stagnated. We must rethink this model and aggressively incorporate promising new treatment models including peer-to-peer mental health and preventative wellness activities like HBOT, Team RWB, and O2X.

We must also empower family members and loved ones to recognize warning signs and encourage treatment. Community engagement—not just government programs—will be the true turning point in ending this crisis.

Conclusion

Veteran suicide is a national emergency—one that demands urgency, transparency, and a unified response. While increased funding, new legislation, and executive commitments show promise, the core challenge remains unchanged: far too many of our nation’s veterans are dying by suicide, and we have yet to shift the trend meaningfully.

Mission Roll Call will continue to advocate for smarter policies, more effective programs, and a deeper national commitment to those who served. Together—with clarity, compassion, and sustained pressure—we can build a system that honors their service not just in word, but in action.