The State of Veterans’ Mental Health [2024]

Since the 9/11 terrorist attacks, more than 3.3 million veterans have served in uniform, with less than 1% of the American population serving during any given year. 200,000 service members transition to civilian life each year, but less than 50% of veterans are enrolled in VA healthcare, making it imperative for the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to change their outreach strategy so veterans receive the health care and benefits they earned and deserve.

An estimated 41% of veterans are in need of mental health care programs every year. Mental health and suicide among veterans is a complicated problem to tackle. There’s no one cause and no one solution. But we do know we need to be more proactive. VA reports have found that veterans are most vulnerable in the first three months following separation from military service, although suicide risk “remains elevated for years after the transition.”

Legislation like the Hannon Act (2020) was an important step toward supporting veterans’ mental health care needs, but there is still much to be done.

In this article, we will discuss:

- What are the most common mental health challenges for veterans?

- What is the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act (Hannon Act)?

- What is the Staff Sergeant Parker Gordon Fox Suicide Prevention Grant program (a.k.a. Fox Grants)?

- Why is the suicide rate higher among veterans?

- How can we support veterans’ mental health?

What are the most common mental health challenges for veterans in 2024?

The most common mental health challenges for veterans are post-traumatic stress (PTS), traumatic brain injury (TBI), depression, anxiety and substance abuse.

Mental health issues can affect every aspect of a veteran’s life. In a 2022 study, 38% of veterans had a code on their medical record for a common mental health disorder. This number does not include undiagnosed mental health conditions, which means the actual number is likely much higher.

Post-traumatic stress (PTS) is a condition that can develop after witnessing or experiencing a tragic or traumatizing event. More than a million veterans have been deployed to combat zones since 2001, and according to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, 15% of military personnel who served in Iraq or Afghanistan experience post-traumatic stress each year. 23% of veterans using VA care have had PTS at some point in their lives.

A JAMA Psychiatry study found that the rate of post-traumatic stress is up to 15 times higher among veterans than among civilians. Symptoms include flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance and physical symptoms.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can also impact mental health among veterans.

Military service members and veterans can experience brain injury from explosions during combat or training exercises. The Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) reported more than 400,000 TBIs among U.S. service members who served since 2000, and more than 185,000 veterans who use the VA for their health care have been diagnosed with at least one TBI.

TBI can cause conditions like headaches, irritability, sleep disorders and depression and can play a major role in veterans’ mental health.

Veterans also struggle with anxiety and depression.

Veterans are five times more likely to experience major depression than civilians, and 3 in 10 veterans with TBI have depression. This can manifest in substance abuse disorders, including alcohol abuse. Some veterans use alcohol and drugs to self-medicate after trauma. Ten percent of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans treated by the VA have a problem with drugs or alcohol.

What is the Hannon Act, and how does it impact veterans’ mental health?

The Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement (Hannon) Act expands mental health care options for veterans through grant programs and and suicide prevention programs, especially in underserved communities.

The Hannon Act was inspired by the service of Commander John Scott Hannon, who retired after a decorated 23-year career with the Navy SEALs. Commander Hannon died by suicide on February 25, 2018, at the age of 46.

The Hannon Act includes:

- Grants that will expand community-based suicide prevention and telehealth services to reach veterans in remote areas.

- Funding for mental health research to identify, improve, and expand treatment protocols.

- A pilot program exploring alternative mental health treatments for veterans, including animal therapy, art therapy, sports therapy, yoga, meditation, acupuncture and chiropractic care.

- The Staff Sergeant Parker Gordon Fox Suicide Prevention Grant Program, which dedicates resources toward community-based suicide prevention efforts for veterans and their families.

Congress passed the Hannon Act on August 5, 2020, and President Donald Trump signed the Hannon Act into law on October 17, 2020.

But there is still more work to be done. More than two years after the Hannon Act was passed, for example, the veteran suicide hotline reached its highest-ever number of calls received. This could be because more veterans are comfortable reaching out for help. More likely, however, is that crisis cases are simply increasing.

It’s not enough to simply set money aside. The VA must take an active role in getting funding for mental health programs to the right people, making sure it is accessible to the nonprofits, businesses and community organizations that are on the front lines of veteran care.

What is the Fox Grant and how does it impact veterans’ mental health?

The Staff Sergeant Parker Gordon Fox Suicide Prevention Grant Program, or Fox Grant, is a part of the Hannon Act. The Fox Grant allocates funding for “on the ground” community organizations that offer traditional and nontraditional suicide prevention to veterans and their families.

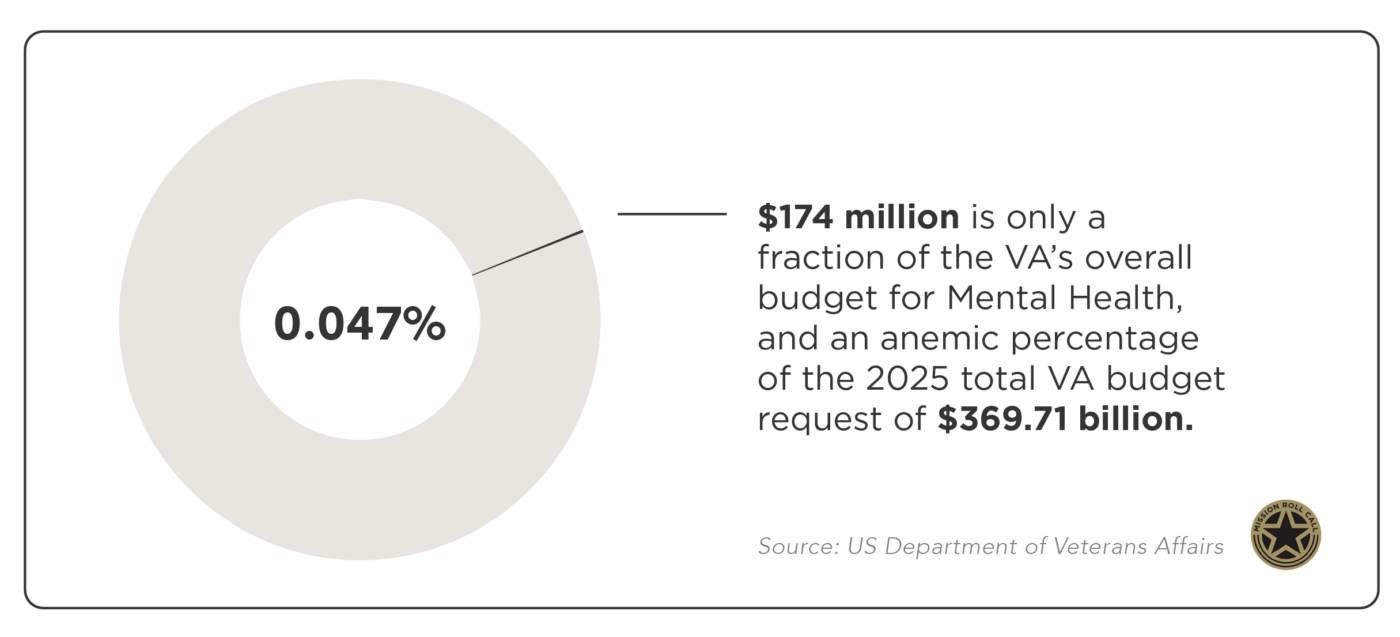

The Fox Grant provided a total of $174 million in resources over three years to veteran-supported community organizations nationwide. The first awards were issued in September 2022, and its final year of funding is FY25.

The Fox Grants have been very successful, but MRC advocates for the FOX Grant program to be permanently authorized beyond FY25 with a more robust appropriation.

Some regulatory changes are needed if the program gets permanently authorized. First, there should be a longer application window for grants. Second, reporting requirements should be tailored to ensure that smaller, valuable organizations can keep up with the workload required by VA.

Additionally, $174 million is only a fraction of the VA’s overall budget for Mental Health, and an anemic percentage of the 2025 total VA budget request of $369 billion. The VA should make veterans’ mental health and suicide prevention its number one overall priority, not just its number one clinical priority. Community organizations are a critical part of addressing this.

As previously mentioned, less than half of veterans in the United States are enrolled in VA care. Some don’t use VA because they have private insurance, others fear going to the VA after all the horror stories they’ve heard, or refuse to use it after a bad experience. Community organizations, particularly in rural areas, may have connections to the veteran community the VA will simply never have.

Additionally, many of the grants have gone to larger organizations. In 2022, for example, 80 Fox Grant awards went to healthcare corporations and state-level organizations.

Smaller organizations often have the ability to form the closest relationships with veterans, and in some cases, they are more likely to know the needs of a specific area or community. And smaller organizations do not typically have as many options for procuring financial support for their programming.

Why is the suicide rate higher among veterans?

The latest VA figures, from 2021, show there were roughly 17 veteran suicides per day, or 6,392 a year; veterans commit suicide at a 57% higher rate than nonveteran adults.

The number of veteran suicides might be even higher than that. One study found that the rate of suicide among veterans could be as much as 37% higher than the numbers reported by the VA.

There are still systemic issues with the VA’s handling of suicide prevention. According to a Mission Roll Call survey, 53% of Americans believe the federal government has “not been very effective” in dealing with suicide among veterans. And 47% believe the government has not been very effective in dealing with transition to civilian life. Tellingly, among Americans who know a service member, those numbers are higher.

The Veterans Crisis Line is a 24/7 helpline (telephone, text messages and online chat) for veterans struggling with suicidal thoughts and mental health. But in September 2023, the Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued a “damning” report of how a suicidal veteran was handled by crisis line staff in 2021. The veteran took their own life minutes after their call to the crisis line ended.

OIG found that the crisis line worker failed to transfer the text conversation to a phone call, contact third-party rescue personnel, or confirm that a family member successfully intervened in the patient’s efforts to commit suicide. The suicide prevention program case manager only contacted the sheriff’s department the next day to request a welfare check. By then, it was too late.

This is just one example of the ways current programs are too reactionary. Outreach and funding to local organizations need to dramatically increase in order to catch veterans at a much earlier point in their spiraled crisis.

The risk factors for veteran suicide, in some ways, look similar to the risk factors for nonveterans: financial stress, substance abuse, mental health diagnosis, problems in a romantic relationship, and unemployment. But there’s one additional critical factor among veterans – an abrupt and often overwhelming loss of community and identity.

There is no uniform “exit strategy” for a veteran transitioning to civilian life.

Many veterans are not prepared for the feelings of loss that come when they are ripped away from the only community they have known for years. Military service touches all aspects of life, from housing to healthcare to social life. When you transition from the military, you don’t just leave your job and your salary. You often leave your house, your city, your friends and your purpose. When you add post-traumatic stress from deployment and combat, it can be a difficult transition.

The best way to combat mental health struggles that come from a loss of community is for community to step in. This is why community organizations that understand and address veterans’ issues are so important.

How can we support veterans’ mental health?

Doctor’s appointments, disability benefits and reskilling aren’t enough to tackle the mental health challenges veterans are experiencing. The Department of Defense and the VA need to fundamentally change the way they approach veteran mental health by taking a more holistic approach to the problem. This starts with being more proactive in addressing the issue.

1. Advocate for all veterans, whether or not they’re using the VA.

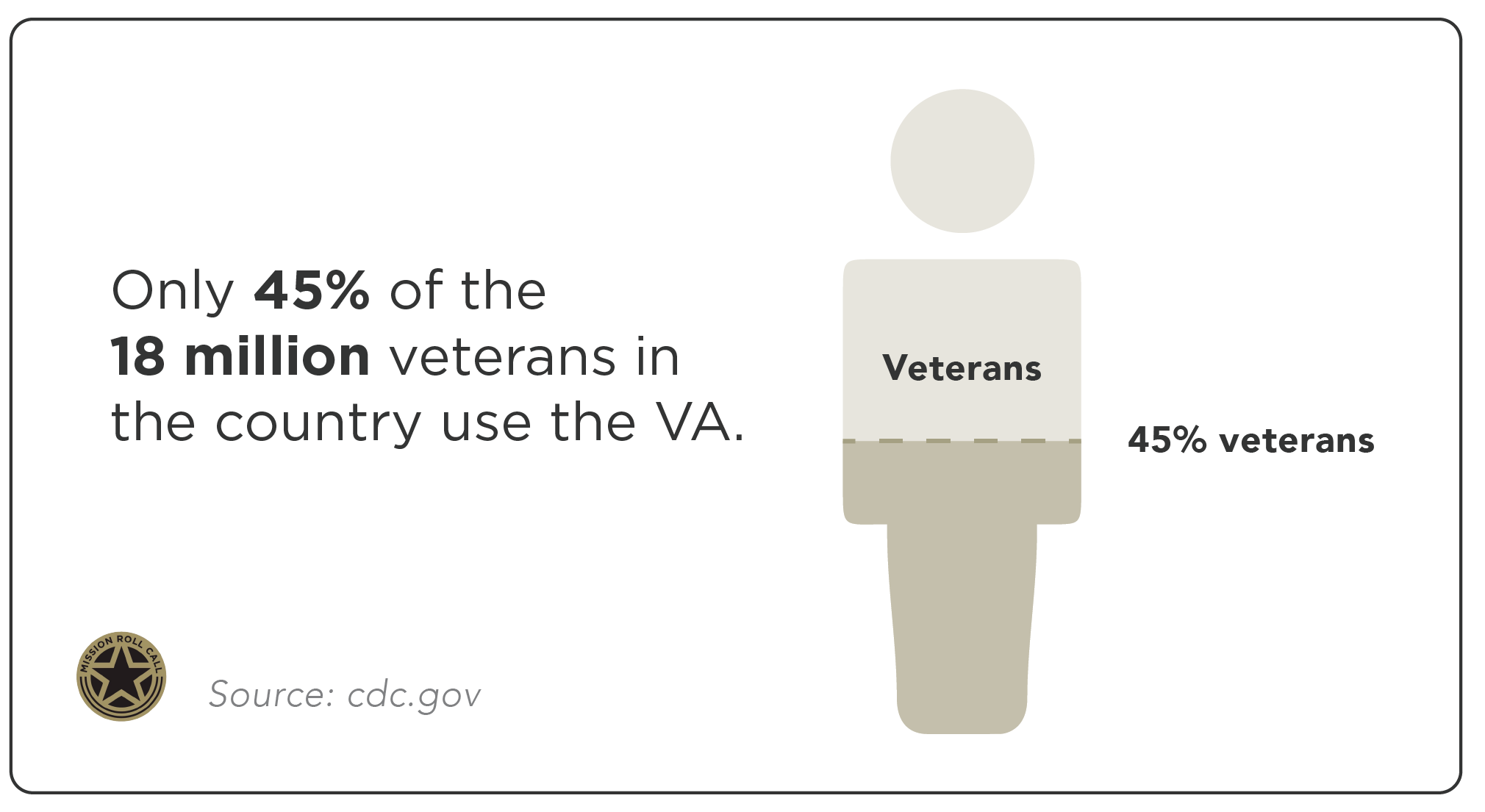

Only 45% of the 18 million veterans in the country use the VA. The best way to tackle the issue of suicide and mental health among veterans is by advocating for policies that provide services to veterans, whether or not they’re engaged with VA services. That’s why policies that fund community organizations that work with veterans are so important.

Mission Roll Call shares stories and news about policies that affect veterans. We also take the views, experiences and insights shared by our veterans and deliver them directly to our leaders in order to speak unfiltered, accurate truth and enact positive change. If you are a veteran or active duty service member or family member, make your voice heard by participating in our monthly polls.

2. Increase collaboration between government and military branches.

Preventing veteran suicide requires more collaboration among the VA, various branches of the military and the Department of Defense. They still have a lot of joint work to do on meaningful transition assistance and things like electronic health record management to make reintegration into civilian life as seamless as possible.

Veteran suicide should be the top priority for the VA. One way this can be achieved is for the Office of Suicide Prevention to be a direct report to the U.S. Secretary of Veterans Affairs, and not housed under the Office of Mental Health.

3. Support meaningful, local connections.

The more we empower community organizations to go find veterans and to work with them, the more we are able to replace connections that were lost after they transitioned out of the military.

Every year, Mission Roll Call visits geographically diverse, veteran-heavy communities across America. We polled veterans in these communities beforehand and were able to compare places like Dallas that had high approval ratings with places like Los Angeles that had low ones. We found that in areas like Dallas, VA officials, nonprofits, and for-profit companies routinely left their facilities to interact with veterans in their communities. They had networks of highly motivated individuals who would find veterans in need and connect them with the appropriate resources.

We can’t wait for veterans to ask for help. Veteran support organizations need to be proactively engaging and getting to know veterans in order to address any small struggles before they become big ones.

4. Spread the word.

Small but effective organizations may not be aware of grant opportunities that exist. The VA needs to invest resources in targeted awareness of these grant opportunities — especially to the communities that their notice claims to prioritize.

Ensuring the application window is long enough for organizations to sustainably and effectively complete all requirements — and that the organizations have an awareness of these kinds of opportunities — will help promote parity among applicants and put necessary funding into diverse veterans communities in need.

Reach out to your representative in Congress and encourage them to advocate for the veterans in your area.

5. Reach out to veterans.

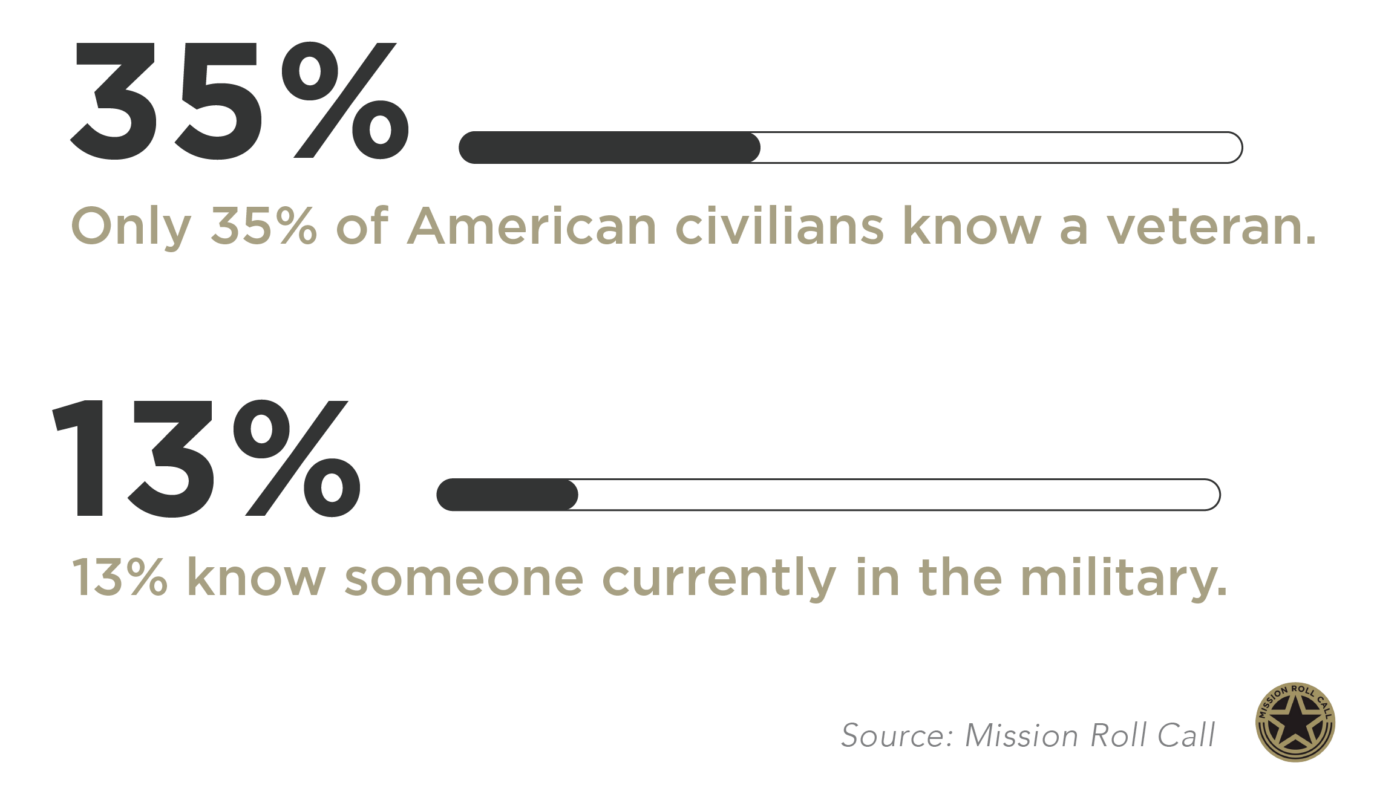

Members of the community have a vital role to play in supporting veteran mental health. But according to a Mission Roll Call survey, only 35% of American civilians know a veteran, and 13% know someone currently in the military.

There are a number of ways to volunteer with veterans in your community and become part of the support network veterans need. Reach out to organizations in your community.

Mission Roll Call has had the privilege of sitting down to hear from many veteran nonprofit organizations, including America’s Warrior Partnership, Black Ops Rescue, Boulder Crest Foundation, Honor Flight Network and more. Find an organization you can help (through donations, advocacy or volunteering) on Mission Roll Call’s Veteran Nonprofit’s list.

Get to know the veterans in your community. It might save their lives.

Conclusion

Congress and the VA have made strides in the right direction toward preventing veteran suicide, but the job is not done until every veteran has access to the resources they need to save their lives.

Not all wounds are visible. Military personnel can be exposed to an array of potentially traumatizing experiences that can impact them for years and decades in the future. With more than four in ten veterans in need of mental health care programs, we need proactive government and community involvement to heal our veterans.

Mission Roll Call will continue to advocate for meaningful legislation, not just so that all veterans have access to quality care, but that this care actually reaches them.

Veterans in need of emergency counseling can reach the Veterans Crisis line by dialing 988 or 1-800-273-8255 and selecting option 1.