Veterans Are Speaking Clearly on Suicide Prevention. It’s Time for a New Strategy.

Despite Decades of Increased Spending, the Veteran Suicide Rate Continues to Rise

Veteran suicide remains a national crisis. Despite decades of effort and billions of dollars spent, the numbers haven’t meaningfully improved. In some areas, they’ve actually gotten worse.

To help shape a more informed strategy going forward, Mission Roll Call recently conducted a national survey addressing the subject of suicide prevention. Over 2,100 veterans, family members, and caregivers from all 50 states responded. Their responses were as clear as they are sobering. But they also pointed toward solutions grounded in lived experience and capable of producing real impact.

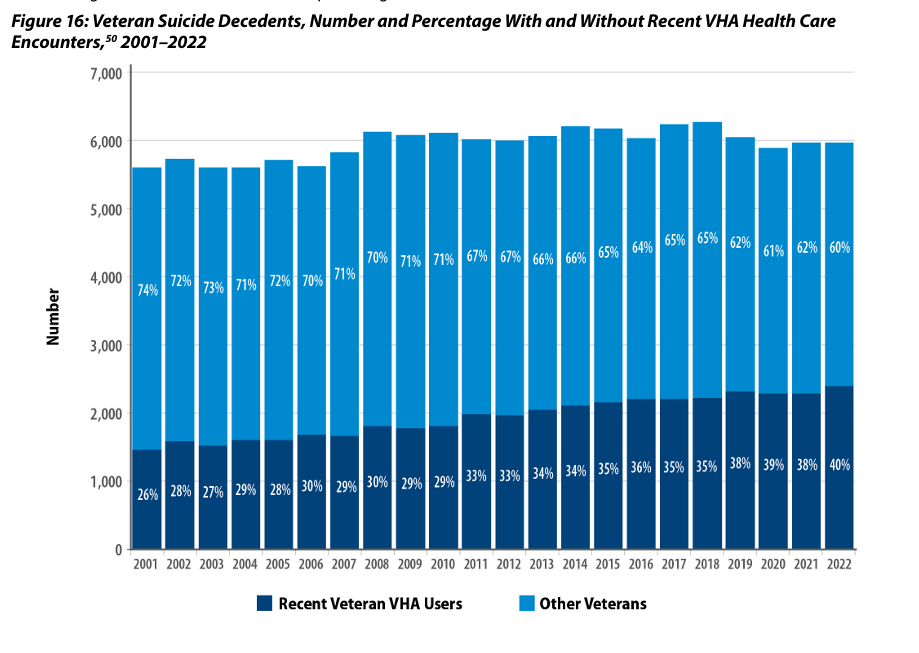

Before we dive into our survey results, it’s important to understand the worsening trend within the staggering numbers of veteran suicides every year. As shown in the chart below from the Department of Veteran Affairs’ 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report, not only do annual suicide deaths among veterans’ approach or exceed 6,000 per year, but the raw numbers are worsening year over year.

A higher percentage of veterans are dying by suicide

While the number of veteran suicides is increasing, the number of veterans is declining. According to the VA, today there are roughly 18 million veterans, down from over 26 million in 2001. This means a higher percentage of veterans are dying by suicide. And as startling as these facts are, the situation may be even more dire. Owing to various challenges in identifying suicide among veterans, the actual number of veterans dying by suicide is unclear and certainly higher than these figures. As just a few examples, county coroners often struggle to identify the deceased as a veteran and there is no mandatory reporting system for county coroners to report to a central database when they do manage to identify the deceased as a veteran. Also, identifying an overdose death as a suicide remains a challenge unless a note or other demonstration of intent is left behind.

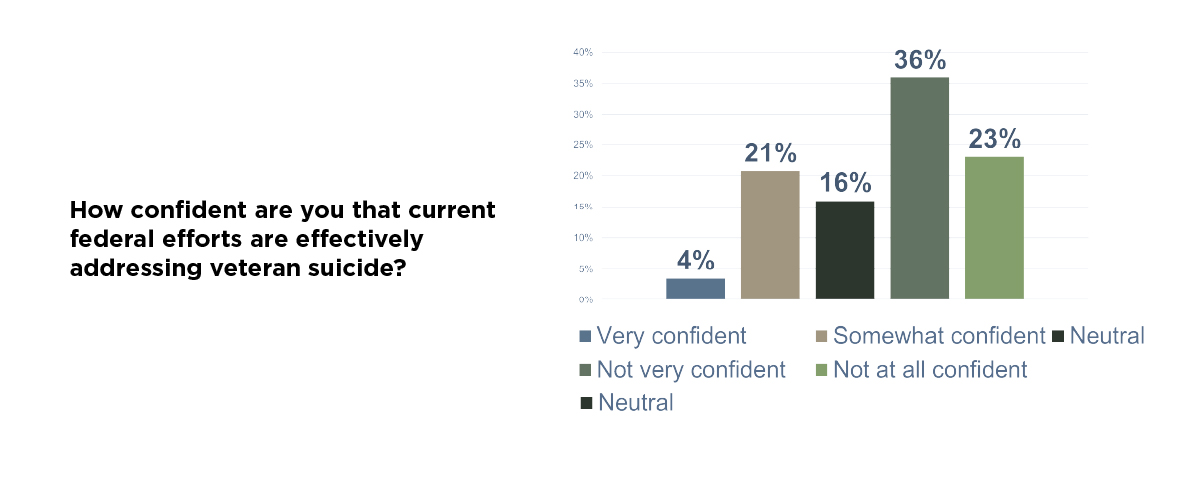

Given this, it makes sense that the VA’s budget allocated to mental health and suicide prevention continues to increase dramatically with each annual budget allocation. That said, these figures, especially when accounting for unknown suicide numbers, demonstrate that current suicide prevention efforts are costing more money and showing worse results.

With that as background, let’s turn to our survey.

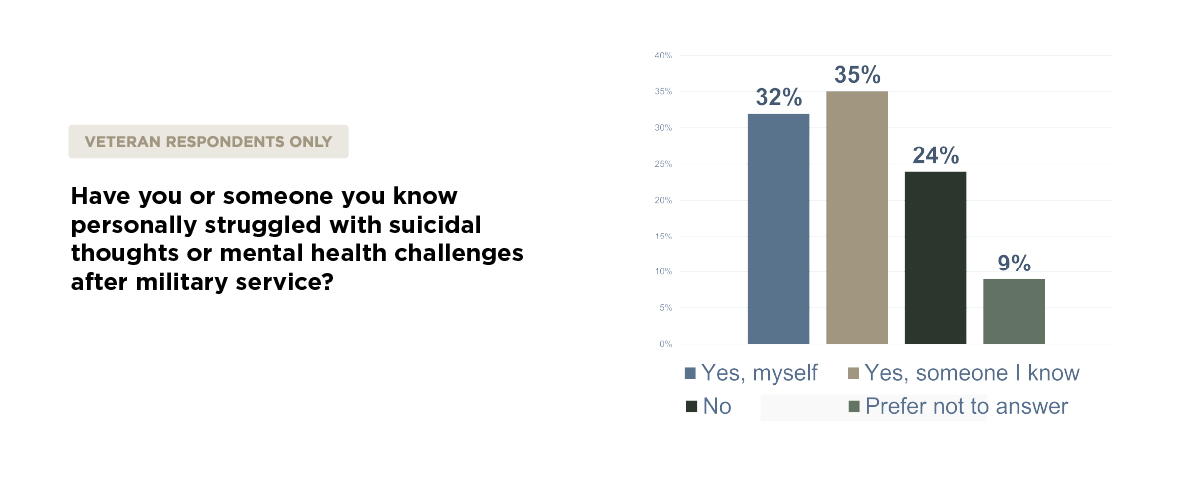

A full two-thirds of veterans struggle with suicidal thoughts

Among only the veteran respondents, a full 67% have either struggled with suicidal thoughts or mental health challenges themselves or know someone personally who has. This figure, extrapolated out over the entirety of the estimated 18 million veterans in the US, means that just shy of 13 million veterans have or might be struggling with mental health challenges or suicidal thoughts.

While the total pool of veterans who might benefit from suicide prevention approaches 13 million, at the same time most veterans express little confidence in the federal government’s current approach to preventing suicide.

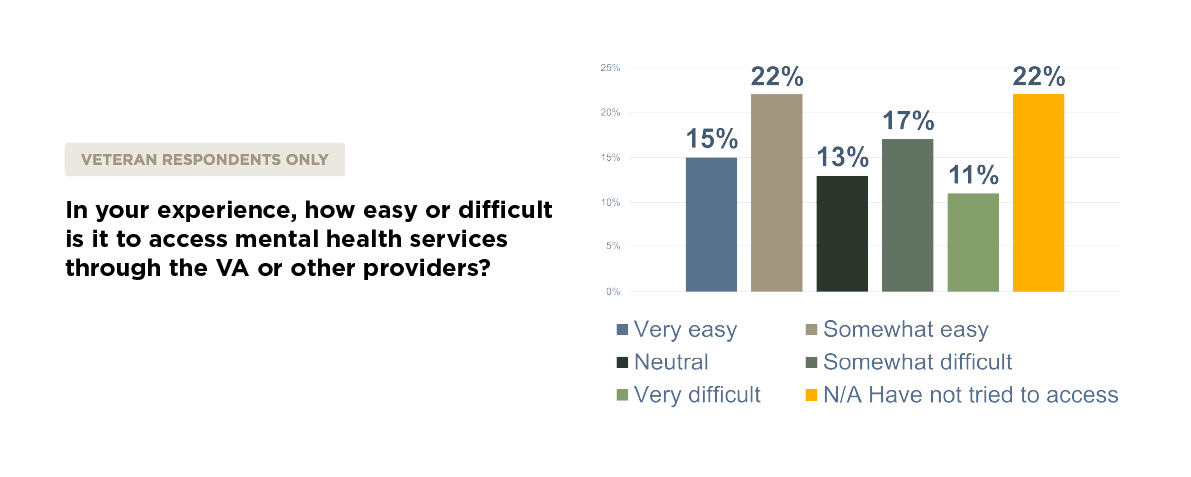

Almost one third of veterans described access to mental health care through the VA or other providers as difficult or very difficult. This aligns with what we’ve heard repeatedly from veterans: the system is often too slow, too bureaucratic, and too disconnected from the day-to-day realities veterans face.

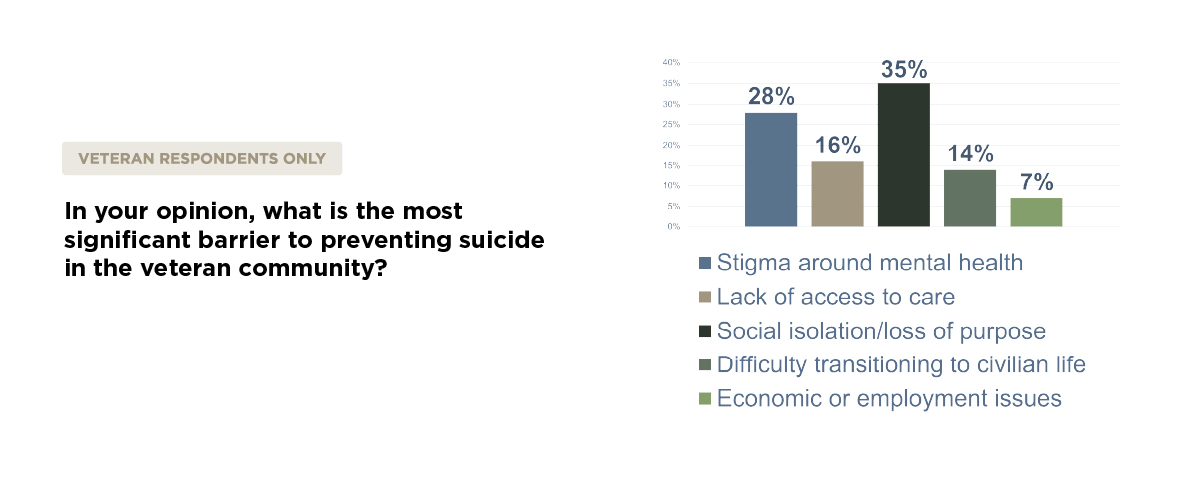

When asked what they see as the biggest barrier to preventing suicide, respondents didn’t point to a lack of funding. They pointed to deeper structural issues—things like stigma around mental health, social isolation, and the struggle to transition into civilian life with a renewed sense of purpose. These are not problems that can be solved by clinical care alone.

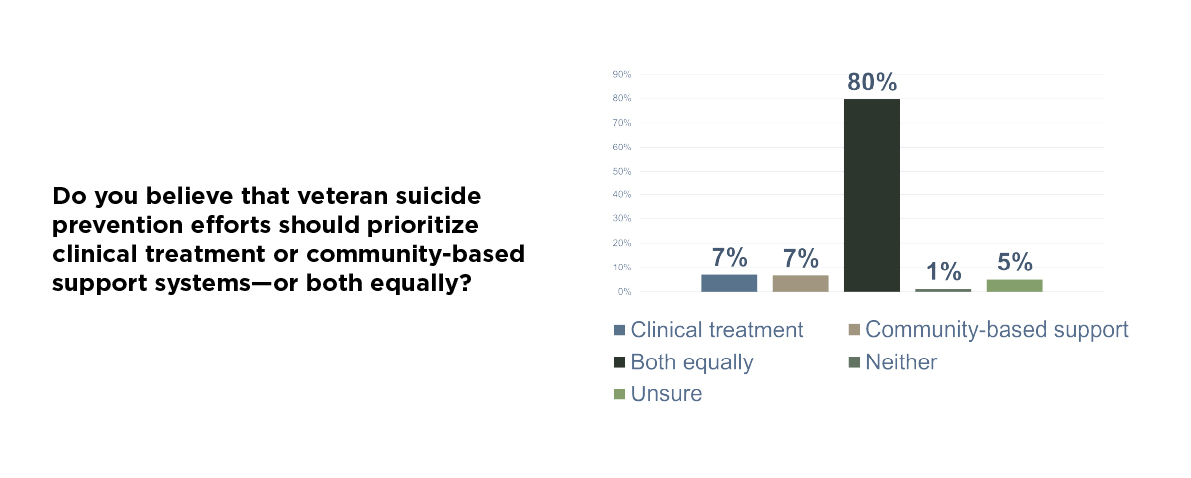

That’s why it’s so important to note what veterans said when we asked them how suicide prevention efforts should be prioritized. A clear majority believe we need both clinical treatment and community-based support, working side by side. This is a strong plea for “all of the above” style solutions and for adhering to the principle of meeting and treating veterans in the manner most meaningful to them.

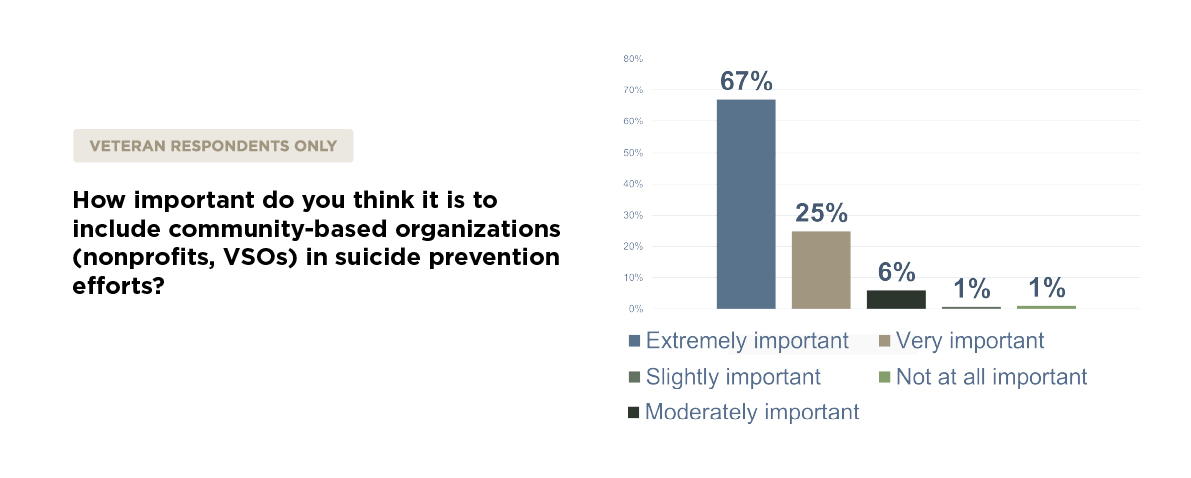

This shouldn’t surprise us. Programs like Team Red, White, and Blue, and The Mission Continues, and other veteran-led initiatives have demonstrated for years that peer connection, physical wellness, and community engagement save lives. And yet, these programs remain underutilized and underfunded.

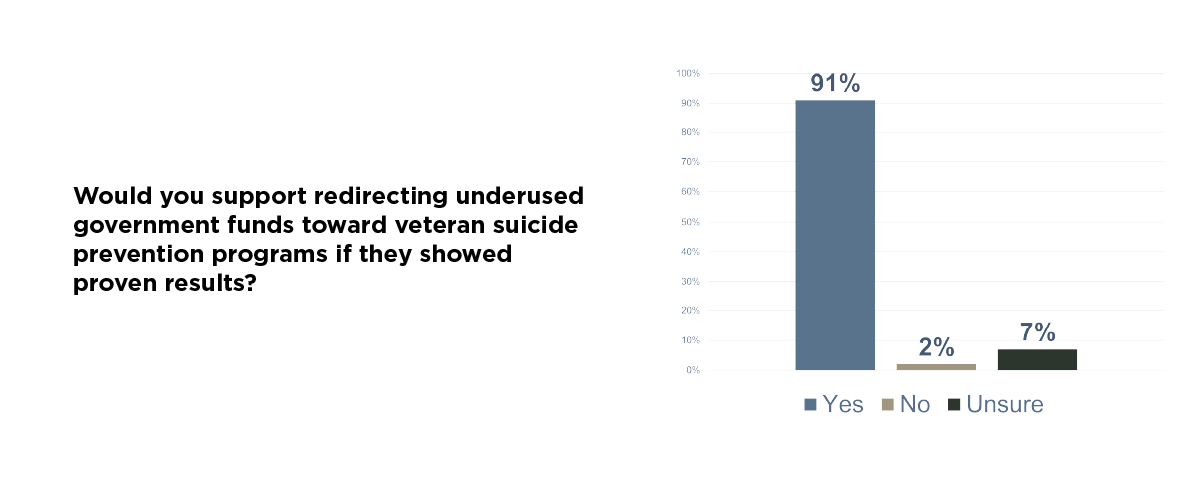

The good news is that veterans overwhelmingly support expanding these types of efforts. They also support creative solutions to pay for them. When we asked about redirecting underused federal funds to support veteran suicide prevention efforts that show proven results, the response was overwhelmingly positive.

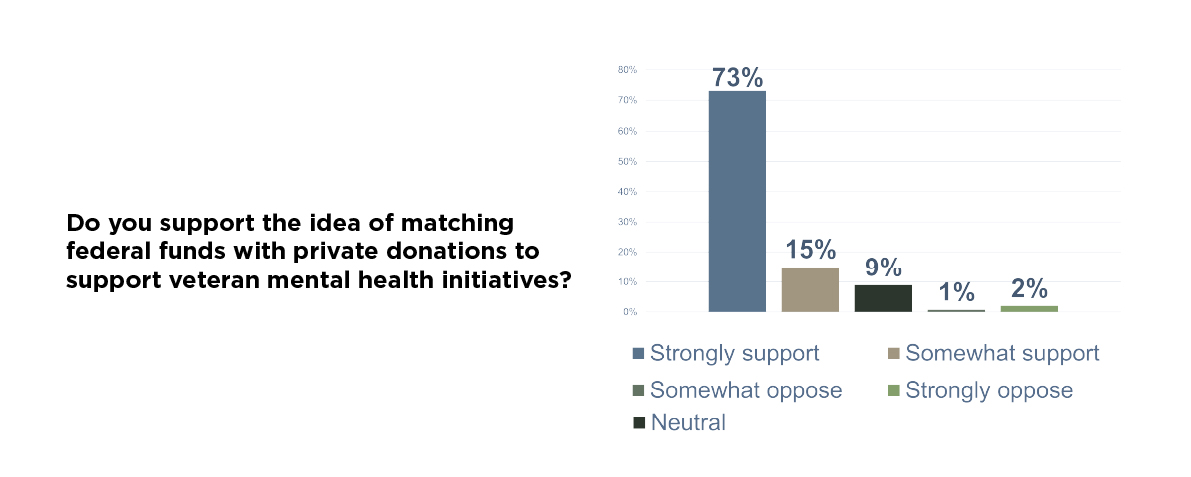

We then asked if veterans would support a federal match for private donations to veteran mental health programs, the answer was again a resounding yes.

These are pragmatic proposals that align with the will of the veteran community and fit within today’s tight fiscal environment. The Fox Grant Program is one example—designed to channel resources into local, community-based solutions. But its implementation has been rocky. Many worthy organizations have struggled to navigate the bureaucracy needed to receive funding. The message we are hearing from veterans is simple: simplify it, expand it, and pair it with a federal match to increase impact.

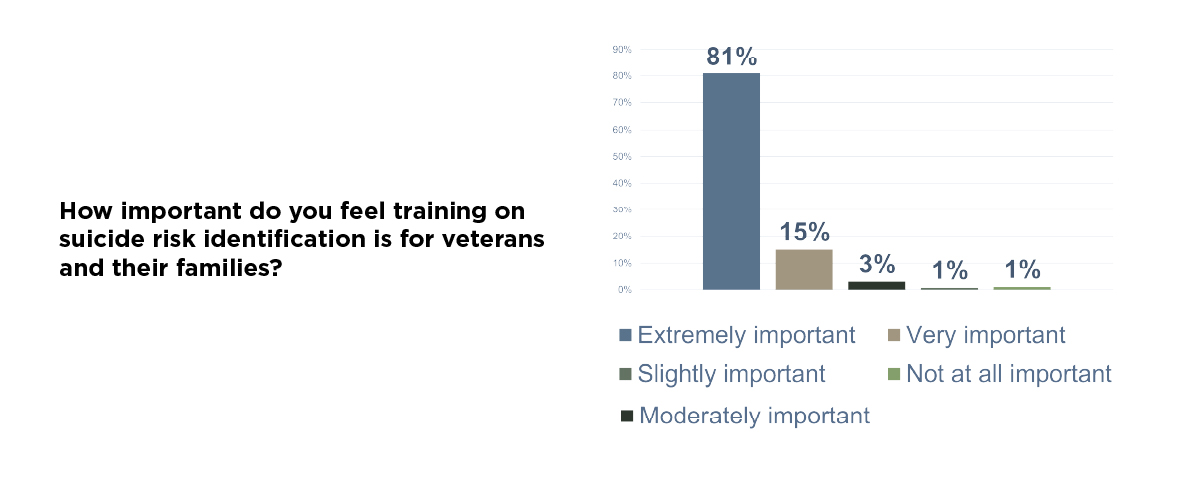

Another area of near-universal agreement? Training. When asked how important suicide risk identification training is for veterans and their families, the overwhelming majority said it was essential. This is low-cost, high-impact work that can be deployed nationwide with the right partnerships in place.

Giving family members and caregivers the tools to recognize early signs of distress can make all the difference. Veterans are far more likely to confide in a spouse, sibling, or close friend than in a clinician or crisis line. Equipping those closest to them with practical training could lead to earlier intervention, stronger support at home, and a greater chance of recovery before crisis strikes.

Veterans don’t want to rely solely on crisis lines. They want the people around them to be prepared and empowered.

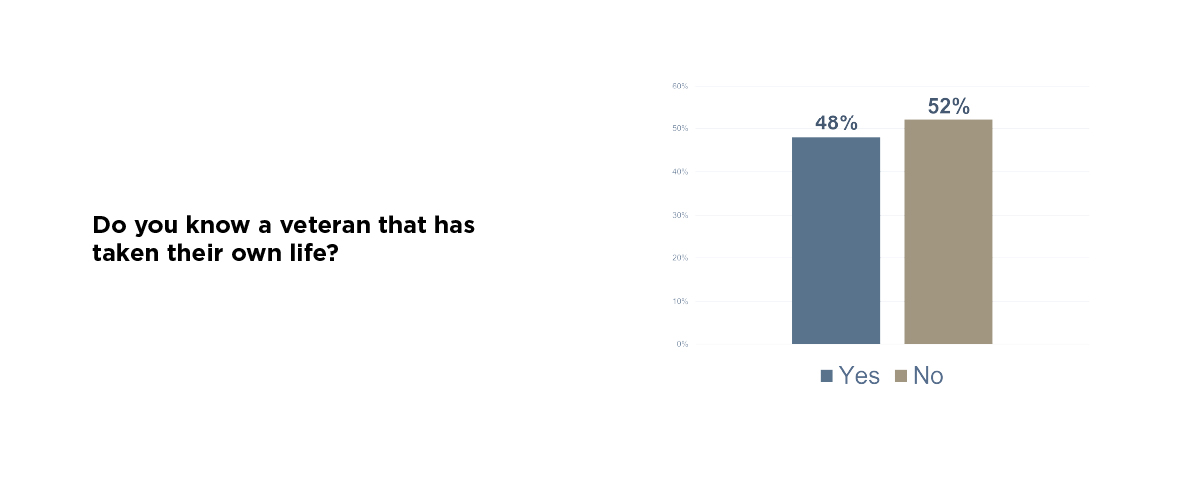

The most personal responses we received weren’t multiple-choice. They were answers to two simple questions: Do you know a veteran who has taken their own life? And as we opened with above, Have you or someone you know struggled with suicidal thoughts or mental health challenges after military service?

The volume of yes answers to both was staggering. These are not distant, abstract issues for most of the veteran community. They are immediate and they are personal. And they are, in many cases, ongoing.

This country has shown that when it decides something matters, we can move fast and think big. We did it with the PACT Act. We’ve done it with housing. We need that same urgency now when it comes to suicide prevention.

Veterans are not asking for more slogans or awareness campaigns. They’re asking for access, purpose, and connection. They want to see the system reoriented toward prevention and away from just managing crisis. They want to be seen not as patients, but as leaders and contributors in building the solution.

We’ve been at this for more than two decades. We’ve spent billions. The numbers haven’t moved. Improving suicide prevention isn’t a funding issue. It’s a strategy, vision, and implementation issue.

It’s time to re-center this fight around what veterans are telling us they need—and what the data increasingly supports. We have models that work. What we need now is focus and follow-through.

Veterans are speaking clearly. The model for addressing veteran suicide isn’t working as it should be. It’s time for Washington to listen.