Afghanistan War Veterans Need More Mental Health Support

One year ago, the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan ended in late August. Thirteen U.S. service members were killed in the evacuation, and — after decades of fighting — Afghanistan was left in disarray. America fought the Global War on Terror (GWOT) to uproot extremists, secure our nation, and in Afghanistan, give the people a chance to choose their own destiny. Recollections of the pullout, and the 9/11 terrorist attacks that sparked the war, can easily trigger anguish among veterans.

As we take in these somber anniversaries as a nation, let’s remember the service and sacrifice our veterans made for their country, and strive to improve their quality of life in the civilian world. Their issues are often not just physical but mental, and remembering the turmoil of last year’s withdrawal can be difficult to reconcile with the honorable service they gave as individuals. Veterans face an ongoing struggle for proper support at home despite putting their lives on the line abroad to participate in America’s longest war. We should use this opportunity to recommit ourselves to their success.

The Chaotic End to the War in Afghanistan

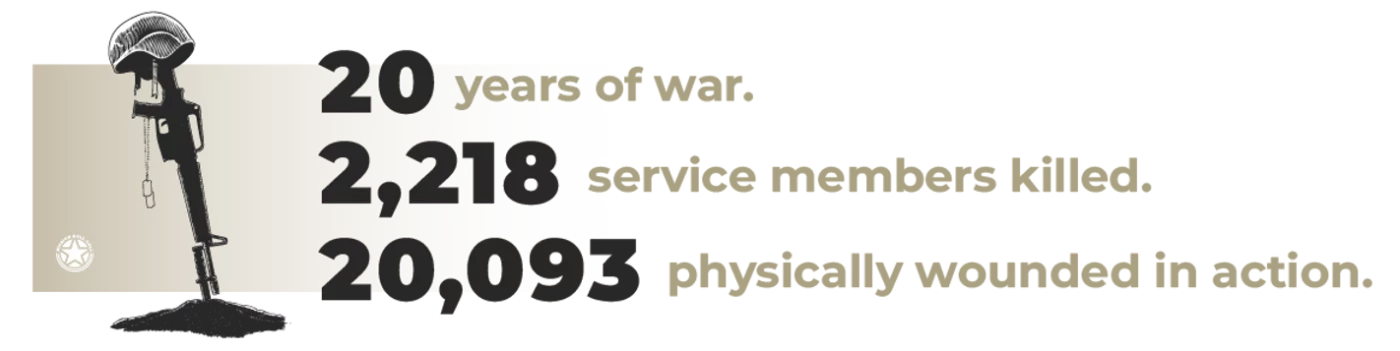

An estimated 3 million Americans served in the GWOT, with missions in Afghanistan and Iraq, among other locations. It began in Afghanistan, when the U.S. government responded to the dastardly attacks on the homeland committed by the terror group al-Qaeda and their leader, Osama bin Laden, who were being sheltered by the oppressive Taliban regime. In the end, 2,218 service members died in Afghanistan, and some 20,093 more were wounded in action.

With the abandonment of the Bagram airfield, the collapse of the Afghan government, and President Biden sticking to an arbitrary August 30 deadline, a chaotic evacuation was guaranteed. The Taliban swept across the country and quickly took control, dismantling the social advancements our military had worked so hard to establish. Adding insult to injury, 170 people were killed — including 13 U.S. service members — by an ISIS-affiliated suicide bomber at Kabul’s international airport.

Why This Affects U.S. Veterans’ Mental Health

The war in Afghanistan had already presented a unique set of circumstances that contributed to the prevalence of post-traumatic stress (PTS) among veterans who fought there. Improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and guerilla warfare tactics, combined with the restrictive rules of engagement that come with fighting an enemy hiding among the civilian population, contributed to PTS becoming known as the “signature wound” of the GWOT. And while improvements in protective gear and emergency medicine increased survival rates, those who were wounded often returned with physical and psychological trauma that veterans of previous conflicts did not.

The VA reports that 11-20 out of every 100 veterans who served in Operations Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Enduring Freedom (OEF) – in Iraq and Afghanistan – exhibit PTS symptoms in a given year. In contrast, about 12 out of every 100 Gulf War (Desert Storm) veterans. There’s also a notable number of OIF and OEF veterans with traumatic brain injury (TBI). An estimated 22% of all OIF and OEF combat wounds were brain injuries, compared to 12% of the combat wounds in Vietnam. TBI can lead to issues such as depression, fatigue, anxiety, and memory loss.

Veterans, in general, are at a higher risk of being diagnosed with PTS than their civilian counterparts, and face distinct barriers to accessing adequate mental health treatment. Data from the RAND Center for Military Health Policy Research reveals that less than half of veterans in need of mental health services receive treatment, and of those who do — for post-traumatic stress and major depression specifically — less than one-third are getting evidence-based care.

And while suicide should not be considered solely through the lens of mental health, the VA’s data shows that veterans reflected a suicide rate 52.3% higher than non-veterans, and for veterans between ages 18-34, the suicide rate is 1.65 times higher than other veteran age groups.

Now, regardless of whether they were physically or psychologically injured, GWOT veterans have to deal with the moral injury that undoubtedly comes after last year. One year later, the Afghan people are living under the oppressive rule of the Taliban, with what can only be described as famine on a Biblical scale. Women and young girls are no longer allowed to pursue their education and must adhere to the strict rules of Sharia Law. U.S. officials have confirmed the presence of terror groups, including al-Qaida and ISIS, operating again in the country. The conditions on the ground resemble pre-2001 Afghanistan, and veterans of the GWOT are left to wonder, “What was it all for?” In a recent Mission Roll Call (MRC) poll, 73% of veterans said the withdrawal negatively affects how they view America’s legacy in the GWOT.

More Support Is Needed for Our Veterans

In time, every GWOT veteran will have to reconcile that moral injury in their own way. That doesn’t mean that the U.S. government and Americans everywhere can’t be more proactive in addressing mental health issues and suicide among our veterans, because the status quo is failing them. Only 50% of veterans use the VA or are affiliated with a veteran service organization. Without the support they need, in the VA or their community, many veterans turn to self-destructive coping mechanisms and are more likely to die by suicide. Changing this tragedy means not only improving mental health services, but ensuring comprehensive support that includes holistic approaches to healing moral wounds, keeping unemployment low, improving transition assistance programs, and directly funding community providers that reach veterans and coordinate care that the VA will never touch.

There should be greater public awareness of the difficulties our veterans are facing. Volunteering for a veteran-serving organization, organizing support groups, mentoring, or providing discounted services to veterans and their families are all great ways to help and show our appreciation.

The veteran suicide rate and the prevalence of untreated mental health issues among veterans should be alarming to us all. While we reflect on the withdrawal from Afghanistan and the 21st anniversary of the Sept. 11 terror attacks, let’s make it a priority to provide support for our veterans and find ways to get involved. It’s the least we can do for those who were willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for our way of life.