Veterans contribute to society in many commendable ways, and the path of entrepreneurship is one particularly impactful example. There are close to 2 million veteran-owned businesses in the U.S., and they employ over 5 million Americans. Despite facing challenges in accessing capital and other areas, 80% of veteran entrepreneurs consider their businesses to be successful.

As we observe Military Appreciation Month and Small Business Month this May, it’s a great time to recognize the contributions of veteran entrepreneurs. They not only support the health of our economy but continue to enrich local communities as well. In this article, we’ll look at ways to support veteran-owned businesses and answer questions such as:

- How many veteran-owned businesses are there in the U.S.?

- What is the success rate of veteran-owned businesses?

- What challenges do veteran business owners face?

- What are some promising trends among veteran-owned businesses?

- How many women veteran business owners are there?

- How can we support veteran-owned businesses?

Overall, despite experiencing difficulties in securing financing, identifying mentors, and navigating regulations and bureaucracy, veteran-owned businesses are reporting success and positive sentiments.

How many veteran-owned businesses are there in the U.S.?

Veteran-owned businesses in the U.S. total nearly 2 million and employ over 5 million Americans. SCORE’s 2021 survey of over 3,000 entrepreneurs found that 9.1% of U.S. small businesses are veteran-owned, and they generate $1 trillion in annual receipts.

Former service members open businesses in numerous sectors, including real estate, construction, retail trade, and transportation. This variety of enterprises helps to meet the needs of their local communities and plays a role in sustaining our economy.

SCORE’s survey findings show that many veterans feel the military prepared them well for small business leadership by developing strengths, like taking on hard work (75.6%) and leadership skills (57.7%). The report also suggests veterans are 35.4% more likely to start their businesses as a supplement to their primary income.

To qualify as a veteran-owned small business, a company must meet the U.S. Small Business Administration’s (SBA) requirements of being at least 51% owned, operated, and controlled by a veteran.

The SBA has two main categories for veteran enterprises: Veteran-Owned Small Business (VOSB) and Service-Disabled Veteran-Owned Small Business (SDVOSB). Having one of these designations is helpful for entrepreneurs seeking to secure federal contracts, as they allow businesses to compete for sole-source and set-aside contracts at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The VA earmarks at least 7% of its contracts each year for certified VOSBs and SDVOSBs. VOSBs can also compete for contracts with other qualifying programs.

The Success Rate of Veteran-owned Businesses

The Institute for Veterans and Military Families (IVMF) 2022 survey of military-affiliated entrepreneurs found that 80% of veteran-owned businesses consider themselves successful, and 54% reported that their businesses were profitable in 2021.

According to the SBA, veterans are 45% more likely to start their own business than the general population. In fact, the number of veteran-owned businesses doubled in 2021, making up 10.7% of new business owners — up from just 5.4% of new entrepreneurs in 2019.

Veterans are known to make not only great employees but also great business owners, and they are more likely to hire other veterans when they start their own companies. With their characteristic discipline, former service members have often been trained in a variety of skills, making them agile, hands-on leaders. They also bring unique experiences to the workplace that can be beneficial for everyone involved.

However, the links between military service and business ownership don’t always lead to smooth transitions for veteran startups. Many service members face challenges in transitioning to civilian life and may not have access to the right resources or networks on the way to becoming a business owner. For example, over 46% of veteran entrepreneurs surveyed by IVMF shared that navigating business resources in their local community was difficult. Hence, becoming a veteran entrepreneur can feel siloed, contributing to limitations in growing and marketing their business.

What challenges do veteran business owners face?

Common challenges for veteran-owned businesses include “developing and utilizing social capital, identifying successful mentors, accessing appropriate financial capital, and obtaining and utilizing business and management skills.”

Despite the ability to adapt to change (a trait that can be useful in keeping up with shifts in their industry or in consumer behavior), former service members may lack the financial resources and business tools to grow their company.

In particular, service members beginning the transition to civilian life may already be overwhelmed with the complexities of securing employment, housing, healthcare benefits, and other necessities that come with a high level of bureaucracy. And those opting for self-employment will need access to resources and networks that may not be readily available or easy to attain.

According to the 2022 National Survey of Military-Affiliated Entrepreneurs, veteran business owners expressed facing barriers in the following areas:

- Financial barriers: Lack of access to capital (37%), lack of financing (34%), current economic situation (27%), and irregular income (22%).

- Social and human capital barriers: Problems finding good employees (30%), lack of mentors (20%), lack of organizations that assist entrepreneurs in business training (12%), and lack of relationships with other entrepreneurs (11%).

- Regulation and policy barriers: Difficulty navigating taxes and legal fees (20%), federal regulations and policies (20%), state regulations and policies (13%), and startup paperwork and bureaucracy (12%).

- Cultural and knowledge barriers: Lack of experience in entrepreneurship or business ownership (18%), fear of failure (14%), personal health issues, such as disability or mental illness (13%), and lack of education about the business world (13%).

- Marketing barriers: Difficulty marketing their business (47%) and conducting market analysis (28%).

The COVID-19 pandemic also presented notable economic challenges to veteran business owners.

A 2021 report from SCORE found that veteran entrepreneurs experienced a lack of support from federal (59.4%), state (76.9%), and local governments (78.5%) and their local communities (52.3%) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though they applied for COVID-19 relief funds at the same rate as non-veteran entrepreneurs, these requests were denied “20%-100% more frequently than for non-veteran business owners.”

Some of the barriers veteran business owners face can be overcome with more community support, such as mentorship, networking events, and consistent patronage. It’s also important for the VA and lawmakers to look toward increasing funding opportunities, business resources, and other initiatives that can open doors for veteran entrepreneurs and aid in the growth of their businesses.

What are some promising trends among veteran-owned businesses?

There are several promising trends among veteran entrepreneurs. Veteran-owned businesses are increasing and showing strong signs of succeeding. According to recent survey data by payroll management firm Gusto, 10.7% of new business owners in 2021 were veterans — up from 5.4% in 2019.

The 2022 National Survey of Military-Affiliated Entrepreneurs found that 80% of veteran business owners consider themselves to be successful, and 72% said they are able to financially support themselves and their families with their business income, compared to 26% that are not able.

Former service members are opening businesses across industries, and many express optimistic outlooks for the growth of their companies. A few of the top sectors for veteran businesses are professional services, construction, retail trade, healthcare, and accommodations/food service.

More doors are opening for funding as well. For example, U.S. Bank recently introduced a new Business Diversity Lending Program that will expand the ability of diverse entrepreneurs to obtain capital, such as women- and veteran-owned business owners.

Women Veteran Business Owners are on the Rise

Women veterans are demonstrating a notable aptitude and interest in entrepreneurship. Currently, 8% of veteran business owners are women, with “an estimated $16.3 billion in [total sales or] revenue, just under 100,000 employees, and about $402 million in annual payroll.”

Based on preliminary data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Survey of Business Owners, the number of businesses owned by women veterans increased by an incredible 296% between 2007 and 2012, up from about 130,000 to a total of 384,548 businesses. And 70% of female veteran entrepreneurs consider themselves to be successful.

Moreover, the signing of Executive Order (EO) 13985 in 2021 marked a historic commitment by the federal government to further support underserved communities, including women veteran entrepreneurs. The VA’s Women Veteran-Owned Small Businesses Initiative (WVOSBI) — providing opportunities and access to economic opportunities for WVOSBs — reports that this order will have a significant impact on the growth potential for female veteran startups.

Allocating $31 billion in new spending on small business programs, WVOSBI explains that this legislation will help:

- leverage intellectual capital and resources to expand services to WVOSBs;

- spark greater collaboration and partnership among WVOSBs;

- increase the participation of federal agencies, nonprofits, and educational institutions in supporting the growth of WVOSBs;

- create more training opportunities geared toward the development of WVOSBs; and

- expand access to economic and educational opportunities for WVOSBs.

How can we support veteran-owned businesses?

Veteran-owned businesses are an important part of our economy and our communities. We can all seek to support veteran-owned businesses by sharing helpful information and resources with veteran entrepreneurs, making an effort to frequent their businesses, leaving positive online reviews, and spreading the word about their products or services.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has a Veteran Entrepreneur Portal for veterans who aspire to be business owners. It includes step-by-step guidance on starting a business, securing financing, government contracting guidelines and other useful information.

The U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) also offers support for veterans seeking to enter the world of business ownership, as well as SCORE’s Hub for Veteran Entrepreneurs and the Coalition for Veteran Owned Business (CVOB), which both offer business mentoring, workshops, webinars and educational resources. Additionally, the PenFed Foundation’s Veteran Entrepreneur Investment Program supports military-affiliated start-up owners in securing capital and offers leadership training.

When looking to find local veteran-owned businesses, you can browse extensive directories such as the National Veteran-Owned Business Association, American Veteran Owned Business Association (AVOBA), Women Veterans Alliance (WVA), Veteran Owned Businesses (VOB), BuyVeteran and the VA’s Vendor Information Pages.

Lastly, be sure to encourage veteran business owners you know to share their stories with Mission Roll Call. Our movement continues to amplify the voices of underserved veteran communities, including service-disabled veterans, women, tribal and rural veterans looking for resources to start or grow a business.

Former service members have shown immeasurable dedication to our nation, and veteran-owned businesses are vital to our economy. These diverse entrepreneurs enrich our communities by providing an array of quality services and products. This Military Appreciation Month and going forward, let’s make it a point to seek out veteran-owned businesses to support, as so many are worthy of our patronage.

This article originally appeared on NBC News

The suicide hotline received more than 88,000 calls, texts and chats in March — the highest amount of monthly contacts it has ever had, new data shows.

The Veterans Crisis Line is fielding a record number of cries for help, the Department of Veterans Affairs said, amid increased mental health concerns for post-9/11 veterans and service members.

The suicide hotline received more than 88,000 calls, texts and chats in March — the highest amount of monthly contacts it has ever had, according to new federal data obtained by NBC News.

Last month’s figure is nearly 28% higher than the busiest of any month in the first 10 months of the pandemic and 15% higher than August 2021, when calls surged after Kabul fell to the Taliban.

“We’re on the front end of a mental health tsunami,” said Scott Mann, a retired Army lieutenant colonel who served three tours in Afghanistan.

The number of annual contacts increased 15% from about 775,000 in 2020 to nearly 896,000 in 2022, VA statistics show. There were about 74,000 total contacts in March 2022, nearly 67,000 in March 2021, and roughly 67,500 in March 2020, according to the data.

In a statement, the VA said there is “no particular data that can be pointed to in order to fully explain the increases” but that a combination of factors, including outreach campaigns and the launch of the crisis line’s new 988 phone number, most likely led more people to use the hotline.

But many veterans said they believe the surge is directly related to the troubled end of the 20-year conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan, which they fought simultaneously and without a draft, meaning they were deployed more than any other generation and for longer.

“Every time you came out of it, you were going right back into it,” said Jonathan Cleck, a former Navy SEAL.

Now, Cleck says, after the longest war in American history, “everything we’ve been able to suppress is now just bubbling up to the surface.”

About 62% of combat veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan said they knew someone who was killed on duty, according to a Pew Research Center survey in 2011.

On top of that, a newly released survey conducted in part by Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, a nonprofit advocacy group, found that nearly 49% of veterans are suffering from trauma as a result of the events of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Army veteran Matt Zeller, 41, a senior adviser with the nonprofit, said he and many others are tormented by extreme guilt over leaving behind tens of thousands of Afghan interpreters and allies — an invisible wound he called a moral injury.

“It’s an injury of the soul,” said Zeller, who served nine months in Afghanistan in 2008. “And it’s the most insidious injury a veteran can suffer.”

Army veteran Matt Zeller served nine months in Afghanistan in 2008.Courtesy Matt Zeller

“There’s not a pill that they can give you. There’s not a group or individual therapy session you can go to. You can’t paint or sing your way out of this,” Zeller added. “It fuels a person to take their life.”

In the immediate aftermath of the Afghanistan withdrawal, the Veterans Crisis Line saw texts for help surge 98% compared to the same time frame the year before, VA officials told reporters at the time.

Among those struggling was Mann, the retired Army lieutenant colonel, who served as a Green Beret for about two decades.

Mann, 54, said he struggled with suicidal ideations in 2013 when he retired from the military and began transitioning to civilian life after multiple deployments. Eight years later, he said, the end of the war in Afghanistan “took me right back to that place.”

“It got pretty dark for me,” Mann said. “The depression came on really hard because of the way the war ended, because of the way our leaders abandoned our allies, and how we were left holding the phone.”

The volume of monthly contacts to the Veterans Crisis Line decreased after August 2021 but spiked again around the first anniversary in the summer of 2022, new data shows. That timing also coincided with the launch of the crisis line’s 988 phone number.

Then, in January, the hotline handled a record high of 85,500 contacts before reaching its peak of 88,000 contacts in March.

Lack of data on post-9/11 veteran suicides

More than 6,800 U.S. military members died during operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, according to the Department of Defense. But because the VA does not track suicides of former service members by generation, there is no way to know exactly how many post-9/11 veterans have taken their lives.

That makes it difficult to find effective solutions, said Cole Lyle, a former Marine and VA adviser who is now the executive director of Mission Roll Call, a nonprofit veterans advocacy group.

“I don’t think you can tackle any problem until you have an idea of the scope and scale of the problem,” Lyle said. “You have to have accurate data, and we do not.”

In at least one widely cited estimate, a 2021 Brown University research paper said more than 30,000 service members and veterans of the post-9/11 wars have died by suicide — more than four times as many as have died in combat.

While the VA’s latest annual suicide prevention report does not distinguish deaths by generation, it appears to show a mental health crisis among the youngest cohorts.

In 2020, the most recent year for which mortality data is available, suicide rates were highest among veterans ages 18 to 34. Suicide rates among that age group increased from 2019 to 2020, while they decreased for all other groups, the report said.

Without accurate federal data, many veterans have been keeping personal tallies, from word of mouth in their social circles. Since the end of the war, Mann said he’s lost three friends to suicide, including one fellow Green Beret and two combat-infantrymen.

Zeller said he knew five veterans who died by suicide directly after the last U.S. service member left Afghanistan in 2021. After that, Zeller did not have the heart to continue counting.

“I stopped tracking,” he said. “I stopped asking the question.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also call the network, previously known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, at 800-273-8255, text HOME to 741741 or visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.

According to a 2020 study by Syracuse University’s Institute for Veterans & Military Families, 91% of surveyed Black and African American veterans reported that military service had a positive impact on their life. In recognizing the numerous contributions of African Americans during this Black History Month, we should also aim to honor the service of Black veterans and find ways to show support to them in civilian life throughout 2023.

Overall, Black veterans enjoy a higher quality of life than Black non-veterans, and many go on to work in security occupations, education, or serve their communities as mentors and local business owners. Still, historical inequities and discrimination have impacted the lives of numerous Black veterans, particularly in relation to accessing benefits and transitioning from the military. In this article, we will explore the following topics:

- How many Black veterans are there?

- What unique challenges have Black veterans faced?

- How can we honor and show support to Black veterans in 2023?

How many Black veterans are there?

The U.S. Armed Forces offer opportunities to Americans of all backgrounds, and our nation’s veteran population reflects this more and more. There are currently an estimated 2,034,818 Black or African American veterans, with the majority living in Georgia, Texas and Florida.

African Americans have fought in every military conflict in U.S. history, even as they experienced segregation, systemic discrimination, and were even denied rights and benefits upon exiting or retiring from service. More than 200,000 African Americans served in the U.S. military forces during the Civil War; over 400,000 served during World War I; and over 900,000 served during World War II.

Although less than 10% of World War II veterans were minorities, since then, each cohort has been more diverse than the last. Of those who have served since the 9/11 attacks, 35% are minorities; with Black veterans making up 15% of post-9/11 veterans and around 12% of the veteran population overall.

In general, there are many promising trends among African American/Black veterans despite discrimination they could potentially face. According to Syracuse University’s Institute for Veterans & Military Families 2020 survey, 89% believe that joining the military was a good decision.

Moreover, 54% said that military service prepared them for their civilian career. The majority also believe their time in service helped them strengthen useful skills such as teamwork (91%), work ethic and discipline (89%), leadership and management capabilities (83%), mental toughness (81%), and professionalism (80%). Black veterans’ earnings are higher on average than Black non-veterans, and their top professional industries include service and security occupations, transportation, management, business, and education.

What unique challenges have Black veterans faced?

One of the greatest challenges Black veterans have faced historically is being denied access to benefits, particularly after World War II. Upon returning home from the war, many Black veterans didn’t receive the benefits outlined in the original G.I. Bill — also known as the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 — that expired in July 1956. This included “low-cost mortgages, high school or vocational education, payments for tuition and living expenses for those electing to attend college, and low-interest loans for entrepreneurial veterans wanting to start a business.”

The bill was intended to help provide economic stability and leverage for World World II veterans, but African Americans were often discriminated against in the implementation of this assistance. By the time the initial bill ended in 1956, 4.3 million home loans had been given out and close to 8 million World War II veterans received subsidized education or training. Yet most Black veterans had been left out of these benefits.

For example, over the period covered in the original G.I. bill (1944 to 1956), African American veterans were often unable to acquire the low-cost mortgages, which allowed veterans to purchase homes in the suburbs whose value would rise significantly in the decades ahead. While this benefit helped create wealth for white veterans in the post-war era, Black veterans were not able to take advantage of this benefit because banks would not offer loans for mortgages in predominantly Black neighborhoods. Furthermore, they were discouraged from purchasing homes in suburban, mostly-white neighborhoods at the time.

Unemployment benefits are another example of how the law was not implemented fairly for Black veterans. Through the G.I. Bill, veterans were guaranteed one year of unemployment compensation with the stipulation of being available until a job offer was extended. Yet post-war, many industries would only hire African Americans for low-wage jobs. When these lower wages were turned down by Black veterans, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) would be informed without context that they were offered a job and did not take it, leading the VA to terminate their unemployment benefits.

Brandeis Institute for Economic and Racial Equity examined the impact of these discrepancies in its March 2022 interim study of the G.I. Bill. It found racial discrimination in implementing the law ultimately “contributed to the racial wealth gap” seen in the socioeconomic realities of today. The report estimates African American veterans received only 40% of the value of benefits that white veterans received. And while the bill’s benefits led to an annual average increase in income of $16,000 for white veterans, Black veterans’ income increases were not comparably or statistically significant.

The VA is taking steps to address these inequities, with more programs and resources dedicated to informing Black veterans and other minority groups of their benefits, such as education and training, home loans, disability compensation, pension plans, and health care.

Current Challenges for Black Veterans

Black Veteran Homelessness: Despite playing such an admirable role in society, a significant number of veterans experience homelessness in proportion to the general population. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates an average of 40,056 veterans are homeless each night, and while only 7% of the general population claim veteran status, they represent 13% of the homeless adult population. Notably, Black Americans overall disproportionately experience homelessness, representing just 12% of the total U.S. population yet 37% of all people experiencing homelessness. There is a similar pattern among Black veterans:They are 12% of the U.S. veteran population, yet 34% of veterans experiencing sheltered homelessness and 26% of veterans experiencing unsheltered homelessness. This is often attributed to affordable housing shortages, unaddressed mental health needs, lack of support networks, or unawareness of federal benefits. Organizations like the Black Veterans Project offer resources and support for Black veterans facing homelessness.

Transitional Challenges: Transitioning from the military and shifting from service-related responsibilities to the demands of civilian life can be a challenge for any service member. African American and Black veterans surveyed by Syracuse University’s Institute for Veterans & Military Families said that securing a job (62%); navigating VA programs, benefits, and services (58%); financial struggles (44%); and managing depression (38%) were among their top difficulties. Notably, more Black and African American respondents (55%) described their financial transition as “difficult or very difficult” compared to white veterans (48%). The majority of Black and African American veterans indicated that their employment transition (59%) was “difficult or very difficult” as well, compared to white veterans (49%). Not only do veterans, in general, need a more comprehensive approach to transition assistance, but Black veterans and other underserved groups must receive tailored support that addresses their unique needs.

Economic and Health Inequities: According to RAND, military service is associated with “more-positive life outcomes and better economic prospects for Black Americans,” including “higher income, improved ability to cover costs of medical and dental care, higher rates of homeownership, and decreased reliance on food assistance programs.” However, though Black veterans often fare better than Black non-veterans in a number of socioeconomic areas, they have yet to achieve economic equity with their white counterparts. Additionally, Black veterans have higher odds than Black non-veterans of experiencing chronic pain, hypertension, high cholesterol, and work-related limitations, which the study attributes to conditions and circumstances surrounding their military service. This underscores the need to ensure Black veterans have access to proper, evidence-based care.

How can we honor and support Black veterans in 2023?

While Black veterans are experiencing positive life outcomes in many areas, there remain inequities that have been fueled by historic discrimination. As individuals, we can call attention to the issues impacting Black and underserved veterans groups by contacting our congressional representatives. Consider writing an email, letter, or tagging your representatives in a social media post that raises awareness around the disproportionate levels of homelessness and transitional difficulties Black veterans are facing.

You can also point Black veterans you know to useful resources and organizations such as Black Veterans Project, VA’s Center for Minority Veterans, and the National Association for Black Veterans.

Mission Roll Call (MRC) is committed to amplifying the voices of underserved veterans groups in Washington with the goal of ensuring access to benefits and quality care. Encourage Black veterans you know to share their story with MRC, as we work to present the unfiltered, unified voice of veterans across America to our nation’s leaders and lawmakers.

The U.S. veteran community is diverse, reflecting the many ethnicities and identities that make up our great country. Black Americans have played a crucial role in the U.S. Armed Forces throughout history — helping to secure our freedoms, breaking down racial barriers, and inspiring our democracy to better live up to its ideals. Black veterans have furthered this impact in life after service as well, so much so that community leaders in Buffalo, New York, unveiled a monument honoring African American veterans in September 2022. And though there is a long way to go to rectify historical inequities, the future holds hope.

As we observe Black History Month, let’s make it a point to recognize the immense contributions of Black service members and veterans while also looking for ways to support them this year.

The 118th Congress took office in January, and there are several timely issues on the table for our nation’s leaders. Although there is some veteran representation among the members, it is still crucial to keep veteran-related policies and issues on their radar. Specifically, the new Congress should prioritize effective veteran suicide prevention initiatives, improved access to healthcare and benefits, and greater support for underserved veterans.

Mission Roll Call is ready to further our bipartisan advocacy around these objectives as our nation’s new lawmakers set an agenda. In detailing the policies, issues, and legislation Congress should prioritize in 2023, this article will cover the following topics:

- How many veterans are in Congress in 2023?

- What veterans issues and bills are on the table for Congress in 2023?

- What veterans policies, legislation, and issues should Congress prioritize in 2023?

- How does Mission Roll Call plan to further advocate for veterans issues in 2023?

How many veterans are in Congress in 2023?

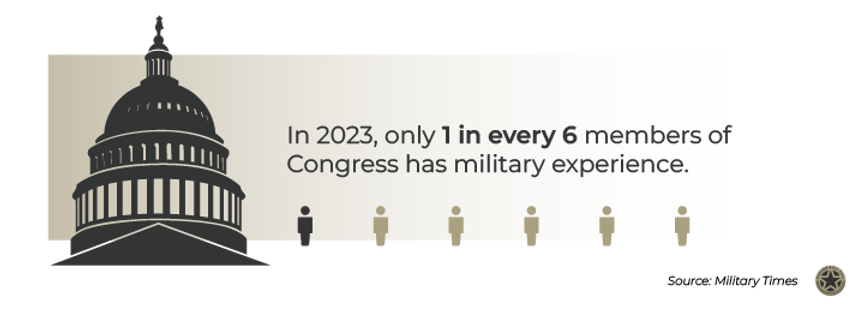

The new Congress has 80 U.S. House of Representative members who have served in the military, reflecting 18.4% of the total congressional membership and up from 75 (17.2%) in the previous House, according to the Pew Research Center. In the Senate, there are still 17 members who are veterans.

Whenever election seasons ramp up, the hope is to elect a Congress that is diverse and, most of all, dedicated to serving the needs of our nation’s citizens. Veterans are particularly deserving of this commitment, as they’ve exhibited immeasurable duty and sacrifice for our country.

The number of veterans in Congress has decreased over the last few decades, declining almost steadily since the mid-1970s when the military began shifting from a pool of drafted individuals to an all-volunteer force. For example, in 1973, around three of every four Congress members had military experience. In 2023, that number has dropped to about one of every six members. The new House has one of the smallest percentages of veterans in recent times (though more than the outgoing body).

The Army, including the Army Reserve and the Army National Guard, is the best-represented branch of the military; over 40% of all the veterans in the House (36 of 80) have served in the Army, the Reserve, or the National Guard.

Another distinction for the new Congress is that women now make up more than a quarter (28%) of Congress — the highest percentage in U.S. history and a significant increase from even just a decade ago. Also, Native American representation is in line with the national demographic; Native Americans are 1% of the overall population and now make up 1% of Congress members.

The makeup of Congress would suggest a greater focus on the issues impacting the demographics represented, but political pressures and agendas can easily take priority. It’s important to stay aware of congressional activities so that we are all empowered to hold lawmakers accountable for addressing the needs of the American public.

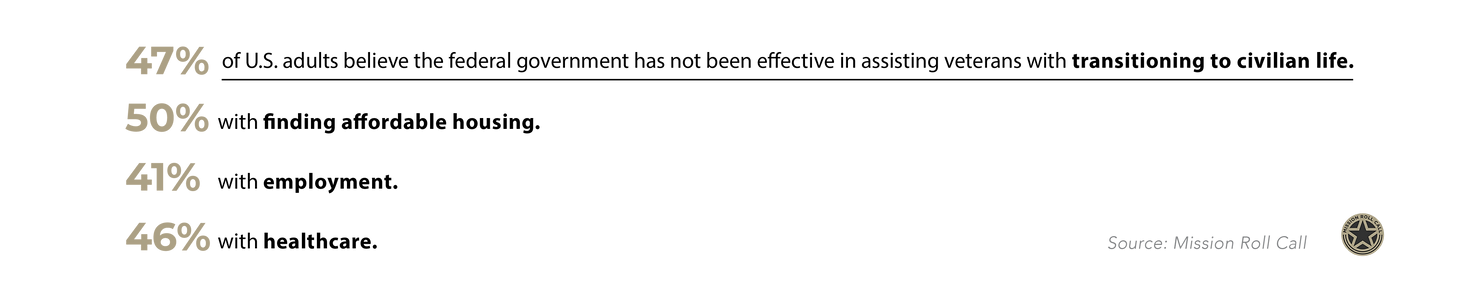

For veterans affairs in particular, there are several matters around suicide prevention and healthcare and benefits access that should be at the forefront of our leaders’ agenda. Our August 2022 research survey found the majority of Americans believe the federal government has not been effective in addressing veteran suicide (53%) or assisting veterans in transitioning to civilian life (47%), and 86% believe Congress should provide quality and expedient healthcare for veterans.

Recognizing the gaps in veteran support, we can collectively work to foster greater awareness and political action around veterans issues in 2023.

What veterans issues and bills are on the table for Congress in 2023?

Welcoming a new year and Congress should remind us that suicide prevention, mental health support, and access to benefits are still issues that demand attention from lawmakers. In 2022, we saw progress on several pertinent veterans issues. This included the passing of the Honoring Our PACT Act, meant to assist veterans who have been exposed to toxic chemicals from burn pits and other sources; the Solid Start Act, requiring the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to contact veterans within their first year out of the military; and the MAMMO Act, focused on improving breast health services at VA facilities.

The VA expanded benefits eligibility to over 3.5 million veterans after the PACT Act passed in August 2022 and also launched a mobile application called VA: Health and Benefits. The downloadable app is aimed at centralizing veterans’ health and benefits information and streamlining navigation of VA services.

More recently, the Biden administration announced that starting in mid-January, veterans in suicidal crisis can receive free emergency medical care at any VA or private care facility. Unlike for most other medical benefits, former service members don’t have to be enrolled in the VA system to be eligible, meaning the new policy could impact over 18 million veterans.

The AUTO Act was also signed into law in early January 2023, allowing disabled veterans who need modified vehicles to receive a grant from the VA every 10 years rather than once in a lifetime; and the VA announced that it will begin waiving all copays for eligible American Indian and Alaska Native veterans, to encourage greater use of primary-care medicine among underserved veteran populations.

Even with these commendable steps taken in 2022 and early this year, there are many policy changes for Congress to consider.

Veterans bills pending in Congress in 2023 include:

- American Indian and Alaska Native Veterans Mental Health Act: This legislation would direct the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to improve suicide prevention and mental health outreach to American Indians and Alaska Natives, as well as to other minority veterans groups.

- Vet CENTERS for Mental Health Act of 2021: This bill is aimed at increasing the number of Vet Centers in various states based on population data. Looking toward better serving the mental healthcare needs of veterans, it would require the VA to ensure certain states establish at least one additional center, and open community-based outpatient clinics.

- Department of Veteran Affairs Provider Accountability Act: This act would amend Title 38 and mandate that the Secretary of Veterans Affairs enforce licensure and professional requirements for health care providers servicing veterans.

- The GUARD Act: Cracking down on lawyer fees for navigating veterans’ benefits claims, this bill would impose criminal penalties on individuals who directly or indirectly solicit, charge for, or receive unauthorized fees or compensation preparing such claims. These offenses could also be punishable by imprisonment.

What veterans policies, legislation, and issues should Congress prioritize in 2023?

In 2023, effective initiatives and legislation are needed around veteran suicide prevention, ensuring access to healthcare and benefits, and supporting underserved veteran communities. The deep implications such issues have in the everyday lives of veterans should inspire Congress to prioritize policies and laws that address these needs.

America’s Warrior Partnership’s (AWP) 2022 Operation Deep Dive interim report found that the rate of suicide among former service members is approximately 2.4 times greater than the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) previously reported. AWP estimates that at least 22 to 24 veterans ages 18 to 64 take their lives each day, and 18 to 20 former service members in the same age group die per day by self-injury — pointing to at least 40 to 44 veterans taking their lives every day.

This data is concerning, and it’s vital that Congress implement effective, holistic prevention initiatives that include transition assistance, job placement programs, funding for community providers, and integrated health treatments (e.g., service or companion animals).

There’s also a serious need to address gaps in veterans’ access to healthcare, lack of awareness around benefits, and low availability of VA facilities in rural areas. RAND Center for Military Health Policy Research shows that less than half of veterans in need of mental health services receive treatment or evidence-based care. And although almost three-quarters (74.3%) of American Indian and Alaska Native service members are enrolled in VA healthcare, tribal veterans living in rural areas often have trouble accessing care because VA facilities are too far or backlogged.

To this end, there must be further federally-commissioned research on the quality of life for rural and tribal veterans and increased federal outreach efforts for these communities. The VA’s Tribal Representation Expansion Project — establishing greater collaboration with tribal governments to expand opportunities for claims representation — is a step in that direction.

Moreover, Congress must ensure the VA adheres to the Mission Act, aimed at strengthening comprehensive healthcare for veterans, particularly the access standards listed in the bill. These guidelines grant veterans the ability to seek care that is in their best medical interest and convenient in terms of location and scheduling. Hence, passing the GHAPS Act would be a good start as it addresses healthcare provisions for veterans via VA and non-VA providers. There must also be increased appropriation for the VA Office of Suicide Prevention — specifically FOX Grants for community-based prevention efforts — and that office should report directly to the Secretary of Veterans Affairs.

Additionally, we want to see Congress focus on implementation and oversight of the PACT Act, to better serve veterans exposed to toxic chemicals from open burn pits and other sources.

In 2023, Congress should double down on such efforts, enact the aforementioned legislation, and give appropriate attention to the many solvable challenges former service members are facing.

How does Mission Roll Call plan to advocate for veterans issues in 2023?

Mission Roll Call (MRC) is committed to furthering advocacy efforts this year on behalf of veterans across the country. Our top priorities — which are reflective of veteran priorities — remain: ending veteran suicide; ensuring veteran access to quality healthcare and benefits; and amplifying the voices of underserved veterans. We take a bipartisan approach to compel all sides of the aisle in Washington to consider the everyday needs of veterans in their decision making.

Specifically, we are determined to push lawmakers to make the following veterans policy improvements:

Veteran suicide prevention: When it comes to veteran suicide prevention, we want to see issues with VA data collection and the management of medical records solved. We call for an expansion of the VA budget for suicide prevention and initiatives that take a holistic approach to veteran suicide prevention, including job placement programs, transition assistance, and funding for community providers.

Ensuring veteran access to healthcare and benefits: Congress must pass the GUARD Act to protect veterans against illegal fees for the processing and preparation of VA benefits claims. Additionally, the VA should provide a clear plan for veterans to navigate the healthcare system with ease, protect and increase community care provisions; and be proactive in improving veteran mental health support.

Supporting underserved veterans: We call on leaders in Washington to create culturally-tailored health initiatives for tribal, rural, and other underserved veteran groups. Wait times for connection to VA providers also need to be reduced, and VA facilities must be expanded in rural areas to help increase the quality of life for local veterans.

MRC is prepared to galvanize efforts on each of these objectives in 2023. Through consistent outreach, polling, on-the-ground fact-finding, our annual research survey, and earned media, we will continue to present the unfiltered concerns of veterans across America to leaders in Washington. For individuals wanting to get involved, we encourage you to push our new Congress to identify and address needs among veterans by visiting your congressional representative’s website and finding out how to make contact via letters or emails. You can also urge them to prioritize veterans issues by sharing one of MRC’s feature stories on social media and tagging your representatives.

Veterans play a vital role in our communities, and we should all consider showing our appreciation. Supporting veterans and aiming to make a positive impact in their lives should be goals for all to work toward in 2023.

The men and women who have served in the U.S. Armed Forces deserve more than our respect—they also deserve appropriate assistance in their transition to civilian life and beyond.

There are many ways to honor former service members for their commitment to our country. As individuals, we can show support by volunteering with organizations that serve veterans, asking our Congressional representatives to prioritize veterans issues, and doing simple acts of kindness.

As a veteran-led advocacy organization, we are determined to further our efforts throughout 2023, and we encourage you to join us. Whether you’re seeking to get involved as an individual, family, business owner, or organization, here are a few impactful ways to support veterans:

- Speak to your Congressional representatives about veterans issues

- Sponsor a service dog to assist veterans with mental health challenges like post-traumatic stress (PTS)

- Express gratitude through simple acts of kindness and giving

- Volunteer to support veterans transitioning to civilian life

- Assist veterans in their efforts to secure employment, education, or affordable housing

- Point veterans in crisis to resources and support groups

- Encourage veterans you know to share their stories

1. Speak to your Congressional representatives about veterans issues

Veterans deserve better from our elected officials and the federal agencies and programs meant to support them. Mission Roll Call’s recent research survey found a number of U.S. adults would agree: 47% believe the federal government has not been effective in assisting veterans with transitioning to civilian life or finding affordable housing (50%), employment (41%), and healthcare (46%).

These survey responses show that many of us believe our leaders and lawmakers could be doing more for our veterans. We must make it a point to let our Congressional representatives know that legislation affecting former service members should be a priority.

There are several ways to make your voice heard. Visit your Congressional representative’s website to find out how to contact their office. From there you can send letters or write emails urging them to prioritize veterans issues during their term and keep up with their track record on related legislation. You can also share a veteran story on social media and tag your representatives. If you’re not sure where to find one, look to Mission Roll Call: We consistently feature veteran stories on our platforms.

Putting pressure on your representatives makes a real difference. In the past year, we saw the passing of the Honoring Our PACT Act, meant to assist veterans who have been exposed to toxic substances; the MAMMO Act, focused on improving breast health services at Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare facilities; and the Solid Start Act, which requires the VA to contact veterans during their first year out of the military.

Even with the positive outcomes expected from these bills, there is much more that can be done to meet the needs of our veterans. Leaders in Congress have a duty to listen to their constituents’ concerns, and your voice matters.

Additionally, you may consider donating to Mission Roll Call. Every dollar you give helps us take the veteran communities’ concerns directly to Washington as we advocate for positive change.

2. Sponsor a service animal for veterans experiencing PTS

Many dogs have been trained to aid and assist individuals with a variety of needs. For veterans experiencing post-traumatic stress (PTS), service dogs may even help ease symptoms such as nightmares, anxiety, depression, or suicidal ideation. A study released in May 2022 by Frontiers in Psychiatry found that “the presence of a service dog improved the reported quality of life, and lowered the level of reported [PTS] symptoms” for veterans.

There are several organizations that allow you to sponsor a companion or service dog for veterans, with packages including training and placement. K9s for Warriors, Patriot PAWS, Semper K9, Warrior Canine Connection, and Labs for Liberty are among those we recommend. Your contribution could have a tremendous impact, whether it’s a monetary gift or volunteer assistance.

Veterans are at a higher risk for PTS than civilians due to certain realities of military life. For example, exposure to improvised explosive devices (IEDs), guerilla warfare tactics, and other horrific acts are known to heighten the chances of developing PTS. Less-mentioned factors like moral wounds, sexual traumas, or issues in military culture can play a role in veterans developing PTS as well.

The PAWS Act, passed in 2021, requires the VA to conduct a five-year pilot program supporting service dogs for veterans with PTS. In an initial step, the VA now allows veterans with PTS and other mental health diagnoses to be eligible for its service dog veterinary insurance benefit.

With research increasingly pointing to the positive effects service dogs can have on veterans experiencing PTS, sponsoring one for a former service member is a great way to show support.

3. Express gratitude through simple acts of kindness and giving

If asked whether we think supporting veterans is a worthy priority, most people would say “yes.” Mission Roll Call’s September 2022 research survey found the majority of U.S. adults believe veterans make significant contributions to their communities.

After selflessly serving in the U.S. Armed Forces, many veterans go on to become vital members of our society in other ways. According to the 2021 Veterans Civic Health Index, veterans are more likely to vote, volunteer, donate to charities, spend time with their neighbors, and be involved in their communities.

There’s no way we can truly repay veterans for their service to our nation, but we can each do our part in showing gratitude. It doesn’t have to be a grand gesture. The great news is there are many practical ways to show appreciation to veterans if you don’t know where to start. Try out simple acts of kindness and giving, such as:

Donating to an organization supporting or advocating for veterans

Whether it’s housing assistance, connecting veterans to quality care, or supporting those in crisis—you are bound to find a local or national organization focused on these needs. Consider making a one-time or regular contribution to a nonprofit doing the work you’re passionate about. For example, in 2022 Mission Roll Call highlighted the work of America’s Warrior Partnership, Boulder Crest Foundation, Camp Southern Ground, and Black Ops Rescue, among many others.

Sending a letter of gratitude to a veteran via an organization

Even with all the rapid forms of communication available to us, there is something special about receiving a thoughtful, handwritten card or letter. Organizations like A Million Thanks and Soldiers Angels will help you send notes of gratitude to veterans. Taking the time to write a thoughtful letter is a great way to honor former service members and put a smile on their faces.

Shopping at veteran-owned small businesses

According to a 2021 report by SCORE, 9.1% of small business owners are veterans and they employ nearly 6 million Americans. Yet the survey of over 3,000 entrepreneurs nationwide found veterans reported a lack of federal, state, and local support amid the COVID-19 pandemic. As we emerge from the pandemic, this is a wonderful time to increase support for veteran-run small businesses. Look for shops or services near you in directories like American Veteran Owned Business Association and Buy Veteran, and aim to make a habit of patronizing them.

Hiring a veteran for your company or organization’s needs

It’s often been said that veterans make great hires. From their characteristic tenacity and discipline to their diverse skill sets and ability to work under pressure, it’s easy to understand why. If you own a business or run a nonprofit organization, consider a veteran for an open role. To get started, visit the U.S. Department of Labor’s website, which features insightful resources and tips for attracting and hiring veteran candidates.

4. Volunteer to support veterans transitioning to civilian life

A recent MRC poll asked veterans if they have received transition assistance (i.e. mentorship, financial assistance, job placement, VA or healthcare assistance) from a local nonprofit, business, or community provider. Out of 4,642 respondents, only 19% said “yes.”

These staggering results show there’s plenty of room to step up and show up for our veterans, especially those transitioning to civilian life.

An estimated 250,000 men and women leave or retire from U.S. military service each year, and the process of adjusting to civilian life can be uniquely challenging for veterans. Things like navigating the healthcare system, applying for jobs, and finding a home can be overwhelming when exiting a career that provided these necessities.

To get started, think of how your skills may be useful to veterans and search for an organization that works in that area. For instance, if you have worked in the medical field, you may want to draw from your experience to help connect veterans with quality care providers. Or if you have great people skills, you could assist the Military Spouse Transition Program or sign up as a mentor for the American Legion.

5. Assist veterans in their efforts to secure employment, education, or affordable housing

Veterans make considerable contributions to the workforce and our communities. According to the latest U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data, the unemployment rate for all veterans (4.4%) was lower than the rate for non-veterans (5.3%) in 2021. And research has shown veterans are more likely to be civically engaged than non-veterans.

Despite playing such a commendable role in society, a significant number of veterans experience homelessness. Only 7% of the general population claim veteran status, yet veterans make up around 13% of the homeless adult population. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates that there are 33,136 veterans experiencing homelessness as of January 2022.

Veteran homelessness is often attributed to affordable housing shortages, in addition to a lack of support networks or unawareness of federal benefits and resources. You can be a part of decreasing veteran homelessness even more by volunteering with organizations like National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, Veterans on the Rise, and U.S. Vets.

What’s more, some veterans have issues securing employment or enrolling in school amid their transition to civilian life.

Obtaining a job that provides the same level of financial security as the military can be difficult. Blue Star Families’ most recent Military Family Lifestyle survey shows respondents listed veteran employment as one of their top concerns. Former service members seeking to enroll in higher education upon exiting or retiring from the military can find navigating benefits and programs overwhelming too.

Unfortunately, the VA’s Transition Assistance Program — known as TAP — is usually not enough to effectively aid veterans in finding employment, education, and benefits. But organizations such as the Boulder Crest Foundation, America’s Warrior Partnership, and Merging Vets & Players offer vital services and support to former service members that can help fill in the gaps.

Take a look at more of the veteran nonprofits Mission Roll Call has partnered with over the years to see where you could be of assistance. There are numerous ways to lend a hand to organizations working to keep veterans securely housed, employed, and empowered to take advantage of educational opportunities—something they all deserve.

6. Point veterans in crisis to resources and support groups

The suicide rate among veterans is concerning. According to America’s Warrior Partnership’s (AWP) 2022 report, between 22 and 24 veterans ages 18-64 die by suicide daily, and 18 to 20 veterans in the same age group die each day by self-injury. This data indicates at least 40 to 44 veterans take their lives every day.

What’s more, Brown University’s Costs of War Project study found that the suicide rate among active service members and veterans of the Global War on Terror (GWOT) is outpacing average Americans; an estimated 114,000 veterans have taken their own lives since 2001.

In 2020, the Veteran Crisis Line (VCL) system was incorporated into 988, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Along with Mission Roll Call, organizations such as Stop Soldier Suicide, Lifeline for Vets, and Mission 22 provide valuable resources for veterans dealing with suicidal ideation as well.

If you know of a veteran experiencing suicidal ideation, urge them to reach out to one of the many organizations designed to help them, such as the resources listed above. Warning signs may include loss of interest in activities, social isolation, expressing feelings of hopelessness, ongoing depressed mood, self-harm, or substance abuse.

Consider volunteering with organizations on the frontline of preventing veteran suicide. You can also reach out regularly to veterans in your life, letting them know you’re there to support them—sometimes a simple call can make a big difference.

Whether connected to a veteran or not, we can all spread the word to raise suicide awareness within our networks.

7. Encourage veterans you know to share their stories

In our aim to present the “unfiltered voice of veterans” to lawmakers and interest groups, Mission Roll Call features stories of diverse veterans from across the country. Encourage a veteran you know to consider sharing their valuable perspective with us.

The collective voice, needs, and experiences of our former service members should be heard by our leaders and representatives, and Mission Roll Call has made it our duty to ensure this happens.

In 2022, Mission Roll Call conducted 19 polls with 92,000 responses from veterans and sent them to Congress. Through consistent outreach, we interacted with over 3,000 veterans and spread the word on veterans issues in 75 media pieces—and that number is growing.

Additionally, we have worked with and referred veterans to several organizations over the years that offer vital services and support, including America’s Warrior Partnership, Patriot Paws, Panhandle Warrior Partnership, Black Ops Rescue, Sierra Delta, Higher Ground, Camp Southern Ground, and Boulder Crest Foundation.

Mission Roll Call’s efforts will continue throughout 2023. As we all map out our plans for the year, let’s keep in mind the courageous men and women who have served our nation and sacrificed so much for our freedoms.

Our team is committed to highlighting veteran stories, educating our members on useful resources, and informing the public and lawmakers on crucial veterans issues. We hope you will get involved too, by supporting former service members in your community through organizations such as Mission Roll Call.

Each year, an estimated 250,000 men and women leave or retire from U.S. military service and return to civilian life. This unique transition can be difficult for veterans and their families for a number of reasons.

Shifting from service-related responsibilities to the demands of civilian life is jarring in-and-of itself, and former service members can find it challenging to relate to family, friends, and citizens who haven’t shared their experiences.

No one knows the impact of these life changes more than the people closest to former service members, particularly their families. This month, as we observe National Veterans and Military Families month, we’re compelled to share the experiences of our former service members and their families, the unique circumstances they face in military life and in readjusting to life after military service, and the contributions they continue to make to their communities.

We recently interviewed Ross Carlson, a veteran of the U.S. Army Airborne. Originally from Homer, Alaska, Carlson served in several deployments as a construction equipment repair specialist. “My transition from the Army was rough,” he shared. “I didn’t think I had resources available to me, and the ones that were available to me just seemed very far removed. It was very much an uphill struggle.” Carlson went on to note that it was ultimately his “military-can-do” attitude and his wife’s encouragement that helped him find his passion again. He now works as a firefighter EMT and has started his own vessel-based excursion business.

Carlson’s journey is just one of many. As he spoke on the various facets of his experience transitioning to civilian life, we learned how crucial it is to give service members seamless access to the resources available to them as they go through these changes. Moreover, the families of service members can benefit from support services as well, since this period can put a great deal of stress on military families.

Service members and their families face stressors during active duty life, like long periods of time apart, or needing to move frequently due to military career demands. But military life also has unique benefits, from guaranteed housing and healthcare to a strong sense of community. When service members leave the military, the shift to civilian life can introduce new stressors.

In this article, we’ll discuss the following topics:

- Is it challenging for veterans to transition to civilian life?

- What effects does transitioning from military life have on families?

- How can we support veterans and their families with transitioning to civilian life?

Is it challenging for veterans to transition to civilian life?

Veterans are a vital part of our communities. After serving our country, their discipline, tenacity, and perseverance shines through as many go into service-based roles in law enforcement, emergency management, medicine, local business, or community leadership.

But although veteran experiences are wide-ranging and not narrowly defined, it is important to highlight the difficulties many endure as they readjust to civilian life. Commonly referred to as the military-to-civilian transition (MCT), transitioning from the military can be one of the most challenging life changes for an individual and family.

There are the practical considerations, such as where to live and what job or career to pursue. While on active duty, service members receive food and housing allowances, in addition to medical care. Going from having these fundamental needs provided for to having to seek them out can be a drastic shift for military families. Navigating the healthcare system, finding a home, and applying for jobs are all things that can be overwhelming when leaving or retiring from a career that provided these necessities and created relative ease in securing them. What’s more, securing a job that assures the same kind of financial security in a new phase of life can be daunting, especially for those with a service-connected disability.

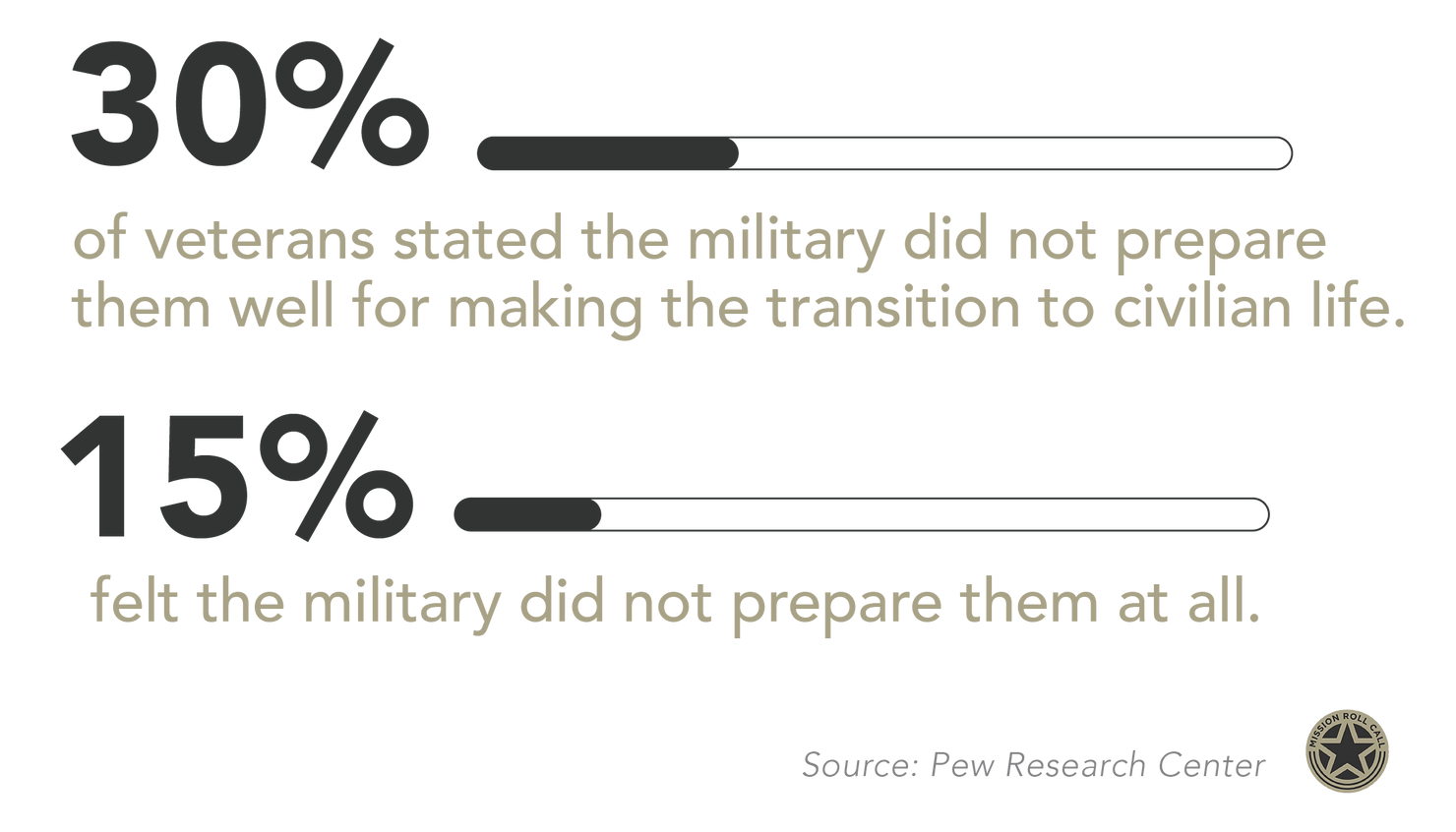

According to a 2019 report from the Pew Research Center on veteran experiences, 55% of veterans who had traumatic experiences and 66% of veterans who have experienced post-traumatic stress (PTS) said their readjustment to civilian life was at least somewhat difficult. Among those with PTS, 3 in 10 said it was very difficult. Moreover, 30% of veterans stated the military did not prepare them well for making the transition to civilian life and 15% felt the military did not prepare them at all.

Post-9/11 veterans in particular expressed more challenges in transitioning to civilian life than veterans who served prior to the Global War on Terror (GWOT). Nearly half of post-9/11 veterans said they found it somewhat (32%) or very (16%) difficult to readjust to civilian life after their service. In contrast, about 1 in 5 veterans whose service ended before 9/11 say their transition was somewhat (17%) or very (4%) difficult. In fact, 78% of pre-9/11 veterans say it was easy for them to make the transition to civilian life, the Pew study found.

Overall, post-9/11 veterans have shown strong employment levels. However, “a greater proportion of those with a service-connected disability experience transition difficulties and a lack of preparedness for themselves and their families.”

What effects does transitioning from military life have on families?

Military life can be both highly rewarding and highly challenging for families, who deserve public recognition for their own sacrifices. Having an active-duty family member often means going without seeing them for long periods and relocating multiple times due to their career demands. It is also well documented that military spouses have historically had difficulty retaining employment because of frequent moves.

But the military also provides some level of financial security, a long-term career path, a wide range of healthcare coverage, considerable retirement and pension plan options, enlistment bonuses, and ongoing professional training. Additionally, military families can take advantage of opportunities to live and serve abroad, educational benefits, better rates on home loans, and child care options. These benefits are not as readily available in the civilian world.

Upon leaving the military, families may deal with the stress of spouse un- and underemployment and out-of-pocket relocation expenses. Healthcare coverage is no longer a given for many transitioning service members and their families, and navigating the complexities of healthcare in the civilian world can be difficult.

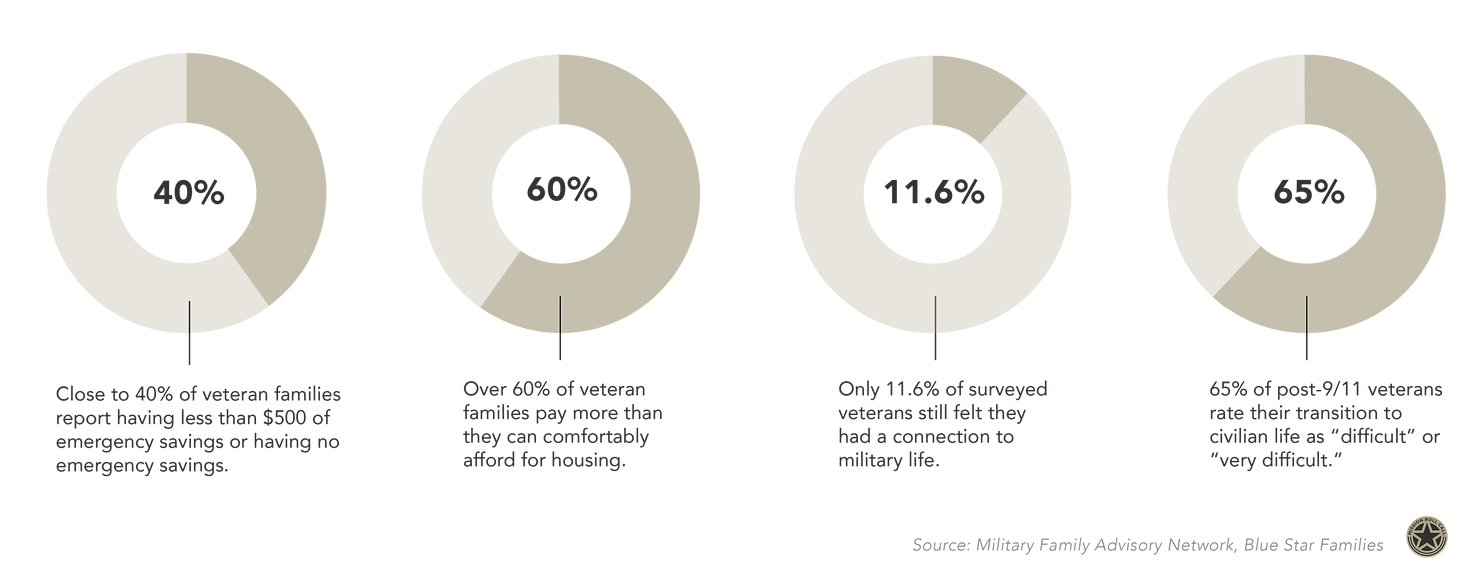

The Military Family Advisory Network (MFAN) surveyed 8,638 military and veteran families for its 2021 report on their health, food security, finances, and housing circumstances. According to the survey, close to 40% of veteran families report having less than $500 of emergency savings or having no emergency savings. Veterans and their families also can experience feelings of disconnection and loneliness; only 11.6% of veterans still felt they had a connection to military life.

On average, civilian families pay $8,355 per child for year-round child care. This can be a considerably high expense to take on for families transitioning from military life, after having full-time, part-time, and hourly care available for their children up to 12 years of age. This benefit includes in-home and daycare services, and for school-age children, military families can take advantage of before- and after-school care as well as free or discounted summer camps. And while the military covers housing costs for active-duty families, the MFAN survey revealed over 60% of veteran families pay more than they can comfortably afford for housing.

Blue Star Families’ survey lists veteran employment, access to military/VA health care systems, veteran and family member mental health, and civilian understanding of veteran issues as the top concerns. And while 68% of employed post-9/11 veterans said they are somewhat or very satisfied with their most recent job, 80% of post-9/11 veterans report a service-connected disability and 65% rate their transition to civilian life as “difficult” or “very difficult.”

How can we support veterans and their families with transitioning to civilian life?

The challenges of transitioning from military to civilian life can be unique from typical life transitions, like entering the workforce, marriage, or retirement. When leaving or retiring from the military and entering civilian life, no two transitions are the same, and every family has distinct needs along this journey.

The Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) Transition Assistance Program, known as TAP, provides tools, information, and resources to service members and their loved ones to help prepare for the transition to civilian life. Service members are expected to begin utilizing TAP around one year before leaving the military, or two years before retiring, yet some have found the program fails to provide practical assistance.

TAP’s broad approach to aiding veterans in finding employment, education, and benefits is not enough. Based on veteran feedback in the Journal of Veterans Studies, more attention should be given to “key areas of their functioning such as adjusting to their new work, educational, [and] cultural settings; meeting family transition needs; financial management issues; procuring housing; dealing with trauma responses; or assuring that veterans truly obtain the benefits and support they need.”

Many in the general public feel this way too. In August, Mission Roll Call commissioned Pinkston to conduct a research survey on Americans’ attitudes regarding a range of veterans issues. Gathering responses from a nationally representative sample of nearly 2,000 U.S. adults, the survey found a significant number of Americans do not believe veterans get as much support from the government as they should. Among those who know a veteran or service member, 47% believe the federal government has not been effective in assisting veterans with transitioning to civilian life or finding affordable housing (50%), employment (41%), and healthcare (46%).

In light of this, Mission Roll Call has referred veterans to several organizations over the years that offer vital services and support, including America’s Warrior Partnership, Patriot Paws, Boulder Crest Foundation, etc. The Military Spouse Transition Program (MySTeP) also offers tips and encouragement to families preparing for the switch to civilian life.

As individuals with a spouse, family member, or friend leaving or retiring from the military, there are many ways people can offer support, such as:

- Helping veterans and their families create new routines and reconnect with extended family, friends, and loved ones.

- Pointing veterans to federal benefits and services and doctors specializing in veteran care.

- Aiding veterans in researching job placement programs, finding employment, or connecting with support groups and organizations.

- Assisting veterans with switching from military-provided benefits to options available to the general public, such as housing needs and setting up services like child care and health care.

Overall, it’s important to be patient and recognize veterans and their families have experiences that are unique from those of everyday citizens. As we commend our active-duty service members and veterans this month, let’s take time to learn more about the difficulties they face at each stage of military life. We all should be encouraged to show support to those who continue to demonstrate incredible selflessness and bravery for our benefit.

Tribal veterans have played a significant role in the U.S. Armed Forces throughout history, yet this community often faces unique challenges in accessing the care and support they need after their time in service.

There are an estimated 160,000 Indigenous veterans across the country, and as we look toward recognizing Native Americans on Indigenous Peoples Day and throughout Native American Heritage Month, it is important to acknowledge the hurdles our tribal veterans experience on a daily basis.

At Mission Roll Call, we use the term “tribal,” though we recognize there are several terms used to describe Indigenous people, including Native American, American Indian, or the names of the many communities within this ethnic group. We have incorporated a few of these with respect to the information referenced and in hopes of highlighting the diversity among Indigenous veterans.

Connected by their deep roots in this land and a complicated history, tribal veterans have bravely served in every major conflict since the founding of our nation. Unfortunately, they often have lower incomes, lower education levels, and higher unemployment than veterans of other ethnicities. They are also more likely to lack health insurance and have a disability – service-related or otherwise – according to the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

Tribal veterans have played a crucial part in serving in the U.S. Armed Forces over time. Like so many of our brave service men and women, their transition to civilian life can be hard. This is not only because of gaps in our veteran care but also due to historical factors that have created social barriers for this group. In this article, we will discuss:

- How many tribal veterans are there in the U.S.?

- What are the unique challenges of Indigenous veterans?

- Is there a high suicide rate among Native American veterans?

- How can we support Native American veterans?

How many tribal veterans are there in the U.S.?

Indigenous people have long been part of the rich fabric of our nation. There are 9.7 million American Indians and Alaska Natives, accounting for approximately 2.9% of the U.S. population.

Historical factors of dislocation, discrimination, and violence have caused grave disparities among Indigenous communities, and even with the majority living outside of reservations today, Indigenous communities are often isolated from the mainstream public. Yet their tremendous resilience and service to our nation can not be understated, having served with distinction in every major conflict, from the Revolutionary War to our most recent conflicts in the Middle East.

There are approximately 160,000 Indigenous American Indian, Native Hawaiian, and Alaska Native veterans across the country. While racial identification can be complex, as of July 2021, there are 14,246 – 1.1% of the total force – who claim to be of Native American ancestry in the active duty force, according to the Defense Manpower Data Center.

American Indians and Alaska Natives serve in the military at higher rates than any other group — five times the national average – and have the highest per-capita service rate of any population.

Exact figures were not recorded, but it is estimated that up to a quarter of all Native American men served in World War I. In World War II, 44,000 of them served (along with 800 Native women in a variety of roles); 10,000 served in Korea, and around 42,000 in Vietnam.

And many Indigenous service members have made the ultimate sacrifice.

Some 30 Native Americans and Alaska Natives were killed in Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan, 2001–2014), with 188 wounded. In Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003–2010), 43 American Indians died while 344 were wounded.

To date, 29 Native Americans have been awarded the Medal of Honor, our nation’s highest military honor. In November 2020, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian opened the National Native American Veterans Memorial, which pays tribute to Native heroes in every branch of the U.S. military.

What are the unique challenges of Indigenous veterans?

Whether returning from service to live on reservations, in rural communities, or in urban environments, many Native American service members are experiencing gaps in veteran care that are exacerbated by unique socioeconomic factors.

There are currently 574 federally recognized Native American tribes in the U.S. Today, 325 American Indian reservations are home to about 22% of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Residents of these areas continue to deal with a poor quality of life, such as a lack of adequate cooking equipment, plumbing, and air conditioning. And though the majority of Native Americans currently live outside of reservations, serious disparities exist among Indigenous communities in general, including:

- Native Americans have the highest risk for health complications.

- Native Americans are the most impoverished ethnic group in the U.S.

- Native Americans are frequently victims of violence, especially Native American women.

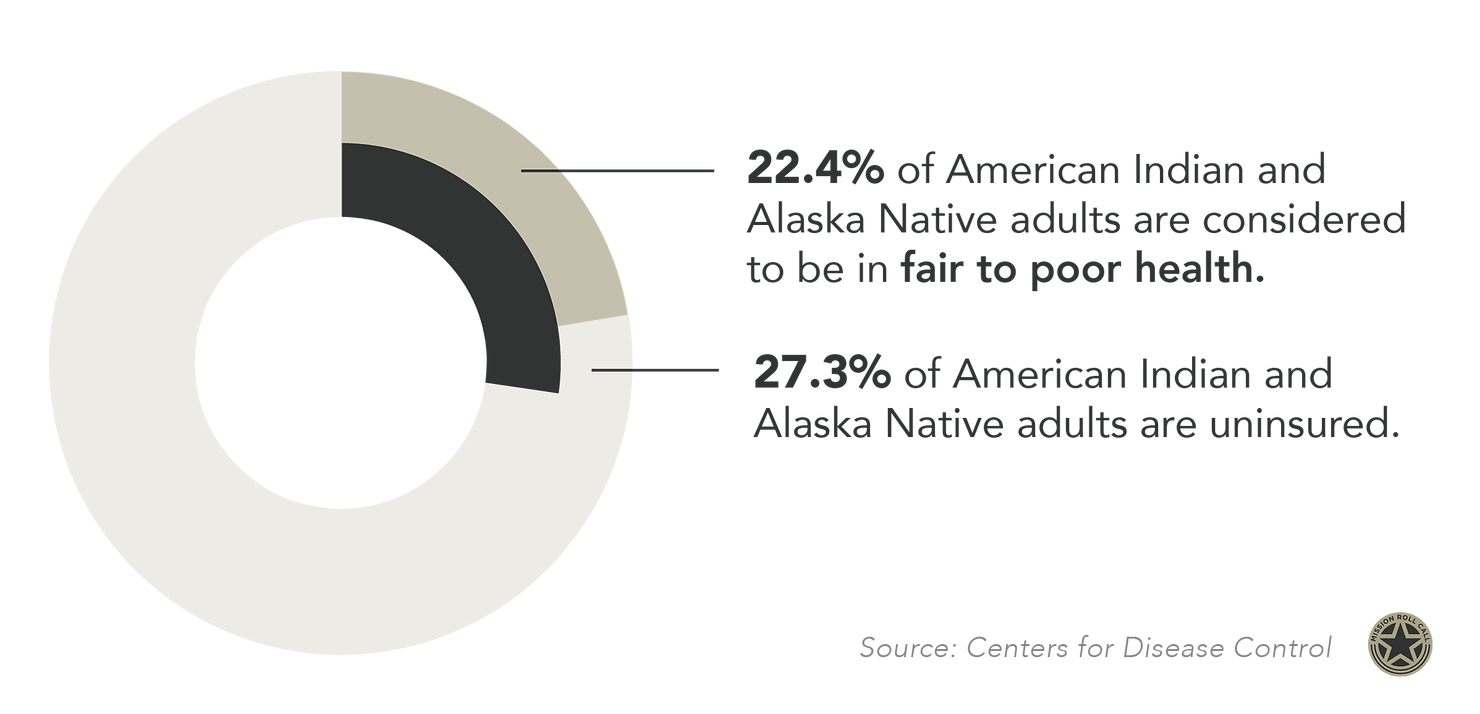

Native American health is disproportionately worse than other racial groups in the U.S., with extremely high rates of heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 22.4% of American Indian and Alaska Native adults are considered to be in fair to poor health and close to one-third (27.3%) of adults in this demographic are uninsured. And although almost three-quarters (74.3%) of American Indian and Alaska Native service members are enrolled in VA health, Indigenous veterans living in rural areas often have trouble accessing care because VA facilities are backlogged or far away. Coupled with combat-related wounds or illness, this can lead to further health disparities among Indigenous veterans.

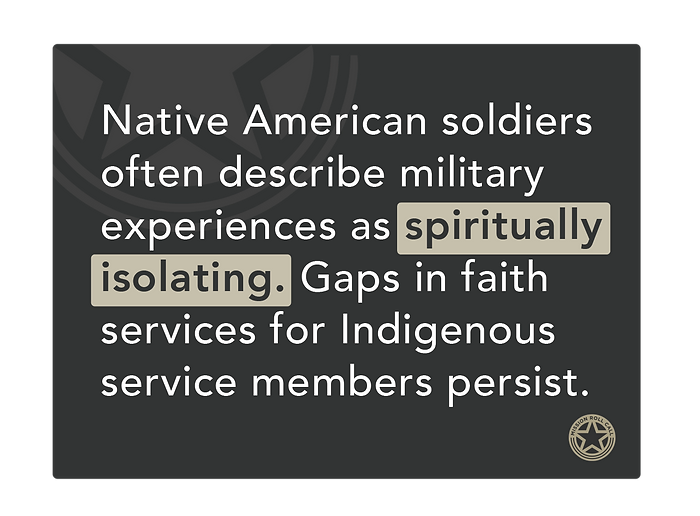

Religious stigmas can impact the well-being of Indigenous veterans as well.

Native American service members have often described military experiences as “spiritually isolating” due to judgments or ignorance around their unique customs. In fact, they were not legally allowed to practice their religion until 1978 with the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA), and gaps in faith services for Indigenous service members have persisted.

In recognizing the impact of these socioeconomic and environmental factors, the VA is seeking to incorporate more “culturally tailored health initiatives” to foster better health outcomes in the Native American veteran community, such as providing alternatives to clinical exam rooms, acknowledging stress related to racial stereotypes, and consulting with tribe leaders for outreach — yet there is much to be done in this regard.

Coming from a community that is facing serious health disparities, high poverty rates, social isolation, and a history of systemic discrimination, Native American service members can often be disproportionately affected by issues in veteran care. As we look to improve support, ensure equity, and provide easier access to benefits for all of our courageous service members, the unique challenges of Indigenous veterans should be taken into consideration.

Is there a high suicide rate among Indigenous veterans?

Suicide and mental health are sensitive issues for anyone to discuss. In the Indigenous community, it’s particularly delicate. While there is still a lack of analysis on the subject, research shows that Native Americans are dying by suicide at a high rate.

Indigenous people in the general population have the highest suicide rates of all ethnic groups in the U.S. Factors such as cultural stigmas, substance use, social isolation, poverty, limited access to health care, and high unemployment rates play a role, along with experiences unique to Indigenous people around historical trauma and discrimination.

For Indigenous service members returning home from their time in service, the numbers are particularly concerning. In 2020, the suicide rate was 30.2 per 100,000 among Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander veterans; 29.8 per 100,000 among American Indians or Alaska Native veterans, compared with 34.2 per 100,000 among white veterans and 14.2 per 100,000 among black or African American veterans.

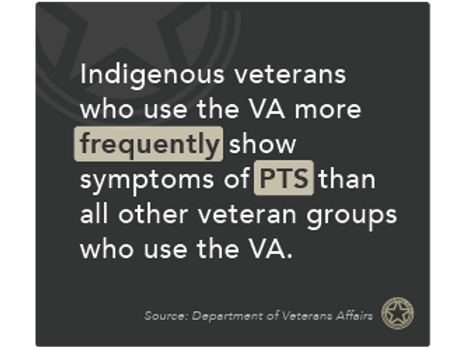

A study published in Medical Care reveals suicide rates among Indigenous veterans receiving services provided by Veterans Health Administration (VHA) rose substantially from 2005 to 2018. Based on the retrospective analysis, for American Indian and Alaska Native veterans who received VHA care between October 1, 2002, and September 30, 2014, the age-adjusted suicide rates more than doubled, rising from 19.1 to 47 out of 100,000 over the 15-year observation period. In the most recent observation period (2014–2018), the age-adjusted suicide rate was 47 per 100,000, with the youngest age group (18–39) exhibiting the highest suicide rate (66 per 100,000).

How can we support Native American veterans?

The well-being of Native Americans is largely shaped by language, culture, and traditions. Because healthcare is closely connected to socioeconomic realities, culturally tailored health initiatives can help improve health outcomes in tribal communities.